MANILA, Philippines — In September, Cheoui de Leon and her husband Luis found themselves stuck on Edsa at 3 p.m.

Traffic flow, as usual, was excruciatingly slow. Then the heavily pregnant De Leon started having contractions.

Between them and the hospital was an endless sea of unmoving vehicles.

“I tried to ease the pain by breathing, but [the heavy] traffic made it worse. I started to shake from the intense pain, but the buses and cars would not let us pass. Every sudden stop seemed to push my baby out,” De Leon recalled.

She gave birth in the car just as it pulled into the driveway of Jesus Delgado Memorial Hospital in Kamuning, Quezon City.

Although her baby was born without any complications, De Leon was aware that things could have easily taken a tragic turn.

“[Heavy] traffic can [lead to] death for people in an emergency [situation],” said the mother of two, who lamented that her long commute also cuts into the time spent with her family.

Little improvement

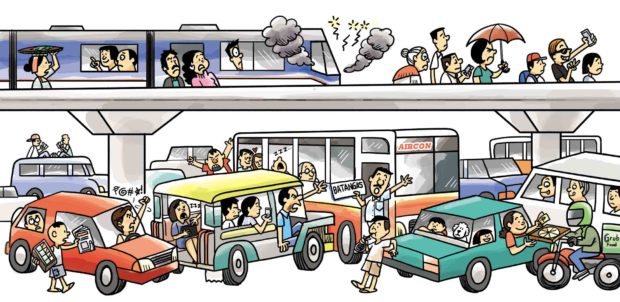

Data coming from the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) showed little improvement in traffic flow on Edsa since 2016.

Last year, it took vehicles an hour, 11 minutes and 54 seconds (1:11:54) to traverse the entire length of the over 23-kilometer-long thoroughfare with an average speed of 19.26 kilometers per hour.

This was down from 1:11:24 and 19.47 kph in 2016, and 2017’s 0:56:15 and 24.62 kph.

Even President Rodrigo Duterte himself considers the congestion on Edsa his sole failure.

“There is no promise I haven’t fulfilled except for the one about Edsa. I promised free tuition, the law is there. I promised free universal health care, I have signed the law. What else do you want?” he said in February.

CAUSE PINPOINTED MMDA Edsa traffic chief Bong Nebrija says that private cars are to blame for the problem. NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

Neomie Recio, MMDA traffic engineering director, attributed the slowdown in vehicular flow to an increase in the number of new cars on top of simultaneous road closures due to projects under the “Build, Build, Build” program.

A representative for a commuter group, however, says the government’s “vehicle-oriented” projects will not necessarily improve mobility.

“These [will] improve the road network capacity for vehicles, but [they will] not necessarily move people. In other countries, they have made moves to veer away from cars and into public transport and bikes, while we’re still focusing on cars,” said Toix Cerna of Komyut.

Built to accommodate 6,000 vehicles per hour, Edsa is now traversed by 7,000 to 8,000 vehicles hourly, according to the MMDA.

While it is not the only road in Metro Manila choking on cars, its proximity to major hubs and link to other major highways make it two to five times more congested than other circumferential and radial roads in the metropolis.

For Bong Nebrija, MMDA Edsa traffic chief, private cars are to blame.

While there were fewer private vehicles in Metro Manila in 2018 (251,628) compared to 2016 (278,657), two-thirds of these pass through Edsa and other major thoroughfares across the metropolis daily.

Single-passenger cars

The MMDA estimated that 80 percent carried just one passenger — the driver.

“Private cars take up so much space but carry so few people compared to buses,” Nebrija said. “We’re trying to take back the roads for the sake of commuters.”

The dismal situation, however, does not seem to daunt the President.

In May, he promised to reduce travel time between Cubao in Quezon City and Makati City to just five minutes by December, forcing the MMDA to scramble for a silver bullet option to realize this goal.

LONGER COMMUTE Last year, it took vehicles an hour, 11 minutes and 54 seconds to traverse the over 23-kilometer-long Edsa compared to 0:56:15 in 2017. —NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

Cerna called it a “crazy, impractical proposition that’s not going to improve the productivity of everybody.”

For the MMDA, it was an opening to start rolling out a series of drastic measures, including bringing back the high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) policy, which banned driver-only cars on Edsa during rush hour.

Nebrija estimated that once implemented, it would reduce by as much as 160,000 the vehicles on the road, enough to grease a 60-kph, nonstop run from P. Tuazon in Quezon City to Guadalupe in Makati City (the closest points between the two cities) within 5.8 minutes.

But when the MMDA implemented a test run of the HOV policy last year, no less than the Senate urged it to reconsider, prompting the agency to drop the idea for now.

Dr. Primitivo Cal of the University of the Philippines said the problem was that the MMDA was attempting to regulate the number of vehicles first.

“These policies have to be rolled out in the correct sequence,” he said. “Improve first the capacity of the mass transport options so that you have room for those who will be affected by these policies. If you roll out the restrictions first, the affected will surely push back,” he explained.

Since last year, the MMDA has also been pushing for a ban on provincial buses and their terminals on Edsa.

Despite the fact that they comprise only 2 to 3 percent of the traffic on Edsa, provincial buses, particularly violators of the “nose-in, nose-out” policy, were too often the cause of bottlenecks on the highway, Nebrija said.

Bus ban hits roadblock

After a test run, the full implementation of the ban was postponed after several lawmakers asked the Supreme Court to issue a temporary restraining order against the MMDA.

The congressmen argued that closing down bus terminals under MMDA Resolution No. 2019-2 called for police powers that were not part of the agency’s mandate.

Still, MMDA General Manager Jojo Garcia was confident that the policy would finally take effect this year once the agency had ironed out its implementing guidelines with the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board.

What is certain for now is that the MMDA has been almost single-handedly, despite some setbacks, trying to improve the traffic flow on Edsa through its yellow lane policy for buses; the no-contact apprehension program for traffic violators; and the unified vehicular volume reduction program.

Cerna’s observation, however, was that the MMDA’s policies were “still biased for vehicles and not for people.”

“The MMDA should review its programs so their appreciation … and approach to solving the problem will also change,” she said.

Cerna added that the MMDA should stop trying to comply with a key performance indicator under its budget, which required it to reduce travel time along major thoroughfares instead of, say, decreasing public vehicles’ waiting time.

She said the ideal ratio for mobility was 10-10-10-3: a 10-minute walk to the transit stop; a 10-minute waiting period; a 10-kph average speed; with a minimum of three transfers.

Thus far, such metrics have not been integrated into the national transport policy by the National Economic and Development Authority, she noted.

“We are trying everything,” Nebrija said. “The thing is, [people] think the MMDA is in charge of everything … when it is just in charge of enforcing regulations.”

Emergency powers

That’s why the MMDA is looking to Congress to pass the emergency traffic powers bill filed by Sen. Francis Tolentino.

Under his version, the transport secretary as traffic czar will have the power to, among others, streamline the tangled policies of local government units on roads like Edsa and C5.

This was crucial as the bulk of the infrastructure projects under the Build, Build, Build program goes into full swing, Garcia said. “But even if the bill doesn’t push through, we will continue doing our jobs,” he added.