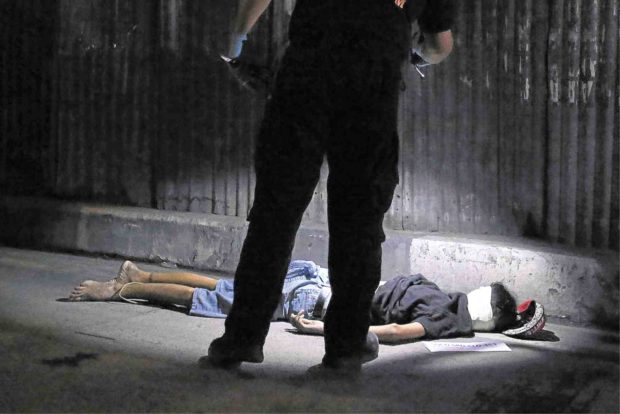

CENTERPIECE PROGRAM Human rights advocates who see the drug war as President Duterte’s chief instrument of control see no end to scenes like this. —RAFFY LERMA

Expect no pause in the body count.

The war on drugs will likely remain the centerpiece program of the Duterte presidency in its last three years, notwithstanding the international notoriety it has earned for the 74-year-old leader, according to human rights advocates.

The reason is obvious: the drug campaign is the President’s chief instrument of control, winning him hometown popularity that has endured three years of bloodshed and persistent global outcry.

“The killings are his political cash cow, so he is not going to abandon that regardless of the condemnation,” said Carlos Conde, researcher for the New York-based Human Rights Watch.

Potent weapon

As a political weapon, the drug war has been potent. “It has changed our political landscape in significant ways,” Conde said, noting how Mr. Duterte centralized power in ways reminiscent of the maneuverings by the family of dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Even before he was elected in 2016, Mr. Duterte had calculated that killings in the drug war would make him popular to the masses clamoring for iron-fisted rule, Conde said. “This is the exact same thing that happened in Davao City,” where Mr. Duterte was mayor for two decades, he said.

Midway through his six-year presidency, “the Duterte family and their closest allies have never been more powerful and entrenched,” Conde told the Inquirer by email.

Emboldened cops

Thus, the administration “mistakenly and stubbornly thinks its approach is correct,” said Edre Olalia, secretary general of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers.

“As a means of control, it has empowered and emboldened the police to make legal shortcuts with brazen impunity and even premium by goading them and patting them on the back,” he said.

The public is then fed propaganda instilling the idea that the drug war is a success, Olalia said.

To that extent, he said, the government has succeeded in framing the brutal campaign as a necessary evil, or at least “deceived people into believing that being sincere is equivalent to being correct.”

Different stats

A December 2018 Social Weather Stations poll showed that while 95 percent of Filipinos consider it important to keep drug suspects alive, close to the same number—87 percent—think that the police feel the same way.

Drug war statistics do not bear this out.

The police reported on Thursday only 5,526 deaths in drug operations from July 1, 2016 to June 30 this year, about a thousand less than what it had reported just a month earlier.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, in a March 9 speech, said “up to 27,000 people” may have been killed during that period.

Foreign affairs officials disputed Bachelet’s figure, but the government’s own 2017 year-end report on the drug campaign listed 16,355 “homicides under investigation” from July 1, 2016 to Sep. 30, 2017, and another 3,967 “drug personalities who died in antidrug operations” from July 1, 2016 to Nov. 30, 2017.

That suggests there were over 20,000 drug-related deaths by Mr. Duterte’s second year despite official denials.

Elsewhere, the killings have stirred outrage.

The UN Human Rights Council had adopted a resolution seeking a full report on the human rights situation in the Philippines. The International Criminal Court is conducting a preliminary examination on whether Mr. Duterte and his lieutenants should be indicted for crimes against humanity in connection with his drug war.

For all that, the Philippine leader has responded with bluster and threats.

David Borden, executive director of the UN-accredited Drug Reform Coordination Network, said Mr. Duterte was emboldened by the public’s favor at home.

Political benefits

He “probably feels he’s still benefiting more politically than the international pressure to date has cost him,” Borden said in an email interview. “The drug war has helped Duterte suppress political opposition, because people who might like to speak out are afraid for their lives.”

Ironically, while Mr. Duterte’s drug war has succeeded politically, it has failed to do what it’s supposed to—control drug abuse, he said.

Borden, an American, remembered meeting a Filipino youth at a UN event in Vienna months ago and asking him what he thought of the drug killings.

“He said ‘it depends on one’s point of view,’” Borden said.

Slide to moral relativism

Such is the danger of Mr. Duterte’s policy of normalizing violence. “Societies should resist the slide into moral relativism. There isn’t more than one legitimate point of view about mass killing,” he said.

Conde said the drug war’s impact would be felt long after Mr. Duterte was gone. “Philippine society will come out of this pretty damaged. I think, perhaps, in the same way that German society was damaged by the lies that led to the Holocaust,” he said.

Ultimately, Olalia said, the public, through civil society and media, must withstand the temptation of growing desensitized to Mr. Duterte’s war.

But how?

“By not looking away,” he said. “By keeping it within the radar of public attention and discourse. By not letting up on calling out the authorities, that they will not get away with it … because there will be accountability in some way, somehow, some time.”