‘Angry glances in the street’: How Paris met Pei’s Louvre pyramid

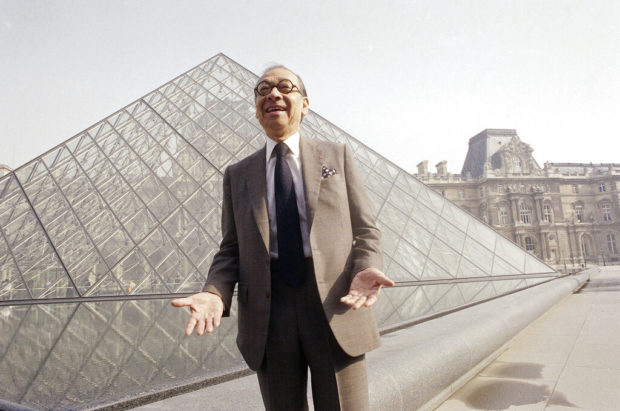

FILE – In this March 29, 1989, file photo, Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei laughs while posing for a portrait in front of the Louvre glass pyramid, which he designed, in the museum’s Napoleon Courtyard, prior to its inauguration in Paris. Pei, the globe-trotting architect who revived the Louvre museum in Paris with a giant glass pyramid and captured the spirit of rebellion at the multi-shaped Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, has died at age 102, a spokesman confirmed Thursday, May 16, 2019. (AP Photo/Pierre Gleizes, File)

PARIS — The modernist architect I. M. Pei, who has died aged 102, was once pilloried for plonking a glass pyramid into the courtyard of the Louvre, but his controversial creation is now a landmark of the French capital.

The Chinese-American designer endured a roasting from critics before the giant glass structure opened in 1989, with up to 90 percent of Parisians said to be against the project at one point.

“I received many angry glances in the streets of Paris,” Pei later said, confessing that “after the Louvre I thought no project would be too difficult”.

Yet in the end even that stern critic of modernist “carbuncles.” Britain’s Prince Charles, pronounced it “marvelous”.

And the French daily Le Figaro, which had led the campaign against the “atrocious” design, celebrated its genius with a supplement on the 10th anniversary of its opening.

In March, the pyramid celebrated its 30th birthday and it remains a cherished architectural landmark.

Pei’s masterstroke was to link the three wings of the world’s most visited museum with vast underground galleries bathed in light from his glass and steel pyramid.

It also served as the museum’s main entrance, making its subterranean concourse bright even on the most overcast of days.

Pei, who grew up in Hong Kong and Shanghai before studying at Harvard with the Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, was not the most obvious choice for the job, having never worked on a historic building before.

But the then French president Francois Mitterrand was so impressed with his modernist extension to the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC that he insisted he was the man for the Louvre.

‘Tact and humor’

The Socialist leader was in the midst of attempting to transform Paris with a series of architectural projects that included the Bastille Opera and La Grande Arche de La Defense, a huge modernist archway in the west of Paris.

Already in his mid-60s and an established star in the United States for his elegant John F. Kennedy Library and Dallas City Hall, Pei was unprepared for the hostility of the reception his radical plans would receive.

He needed all his tact and dry sense of humor to survive a series of encounters with planning officials and historians.

One meeting with the French historic monuments commission in January 1984 ended in uproar, with Pei unable even to present his ideas.

“You are not in Dallas now!” one of the experts shouted at him during what he recalled was a “terrible session,” where he felt the target of anti-Chinese racism.

He had won the Pritzker Prize, the “Nobel of architecture,” in 1983, but even that didn’t seem to assuage his detractors.

Violent reaction

Jack Lang, who was French culture minister at the time, told AFP he was still “surprised by the violence of the opposition” to Pei’s ideas.

“The pyramid is right at the center of a monument central to the history of France,” he said, referring to the Louvre’s former role as a royal palace.

“The project also came at a time of fierce ideological clashes” between the left and right, he added.

A whole wing of the Louvre was then occupied by the French ministry of finance. The museum’s huge “Napoleon Courtyard was an appalling car park,” Lang said.

But the Louvre’s then director, Andre Chabaud, resigned in 1983 in protest at the “architectural risks” Pei’s vision posed.

The incumbent, however, is in no doubt that the pyramid is a masterpiece that helped turn the museum around.

Jean-Luc Martinez is all the more convinced of the fact having worked with Pei over the last few years to adapt his plans to cope with the museum’s growing popularity.

Pei’s original design was for up to two million visitors a year. Last year the Louvre welcomed more than 10 million.

For Martinez, the pyramid is “the modern symbol of the museum,” he said, “an icon on the same level” as the Louvre’s most revered artworks “the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace”.

Pei is not alone in being savaged for changing the cherished landscape of Paris.

In 1887, a group of intellectuals that included Emile Zola and Guy de Maupassant published a letter in the newspaper Le Temps to protest at the building of the “useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower”, an “odious column of sheet metal with bolts.” /kga

RELATED STORY