PH pastor fights for gay marriage in HK court

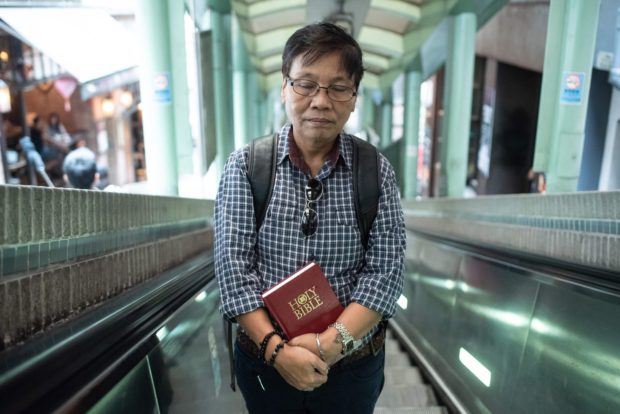

HONG KONG — As a transgender pastor of a small Hong Kong church that welcomes all sexualities, Marrz Balaoro wants to conduct religious marriage ceremonies for same-sex couples but fears arrest, a battle he is now taking to the courts.

Despite growing support for gay marriage in the international financial hub, campaigners have made little headway against stiff opposition from the city’s successive pro-Beijing governments and religious conservatives.

But now an unprecedented legal challenge filed by the Filipino Reverend Balaoro turns the more commonly heard religious argument opposing gay marriage on its head.

In a filing with the city’s High Court, he argues that his congregation’s freedom to worship—a right enshrined in Hong Kong’s miniconstitution—is being trampled on by the city’s ban on same-sex marriages.

“All we ask for is to be allowed to worship and practice our religious faith in the eyes of God, free from the threat of persecution,” Balaoro explained.

Article continues after this advertisementArrested in 2017

Article continues after this advertisementThe 62-year-old pastor, who has worked as a domestic helper in Hong Kong since 1981, knows that threat all too well. In 2017, he was arrested on suspicion of breaking Hong Kong’s marriage laws for officiating “Holy Union” ceremonies at the city’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Straight (LGBTS) Christian Church.

The denomination originated in the Philippines but has a small following among gay domestic workers in the southern Chinese city.

The union ceremonies were religious blessings for same-sex couples with no legal weight. Prosecutors eventually dropped the case.

But despite repeated attempts, Balaoro was unable to get written assurances from Hong Kong authorities that he won’t be arrested again should he conduct another union.

His legal application seeks a court declaration that such same-sex religious ceremonies are not illegal.

Balaoro is clear his church’s same-sex ceremonies have no legal substance under Hong Kong law, but he says they carry great spiritual importance for his flock.

“They know this is just a celebration of love and togetherness,” he told Agence France-Presse, describing the occasions as “joyous.”

Hong Kong does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions and decriminalized homosexuality in 1991.

But a British lesbian won the right to live and work in Hong Kong with her partner in a landmark ruling last year hailed by rights groups.

A separate case has been lodged by two Hong Kong men directly challenging the same-sex marriage ban as unconstitutional.

Unusual case

Balaoro’s application is unusual because it includes a freedom of religion argument.

In the filing requesting the court to hear their case, his lawyers said current legislation restricting the “celebration of the religious rite of marriage only to heterosexual monogamous couples” is discriminatory.

Balaoro and his parishioners are “treated differently on the basis of their religion, to their detriment.”

Originally from the Philippine province of Abra, Balaoro has identified himself as a male since the age of 5.

“When I was younger, my parents could not even impose on me to wear dresses and skirts, not until I went to a private Catholic (girls’) school . . . I wore shorts under my skirt, and I wore a T-shirt under my long-sleeves, and I took off everything on my way out of the school campus,” he said with a laugh.

On top of his full-time job as a domestic worker, he became a pastor in 2013, established the Hong Kong branch of the LGBTS Christian Church a year later, and was ordained as a reverend in 2017.

Duty to community, others

Born into a Catholic family, he stopped going to church during his high school and college years, citing the discrimination he faced.

But when he later encountered the slogan of the LGBTS Christian Church—“you are accepted for who you are, and safe for what you are”—he found his calling to propagate faith with advocacy.

“I think it is my role, it is my duty, not only to the LGBTS community but to all people out there (to say) that we exist and there’s nothing wrong with us.”

There are nearly 370,000 migrant domestic workers in the city mostly women from the Philippines and Indonesia, often performing menial tasks for low wages while living in poor conditions.

Gay domestic workers, Balaoro says, are especially vulnerable, often facing discrimination at other churches. “The support we need is to defend us, to support our cause, to respect our gender identity. That’s what matters to us.”