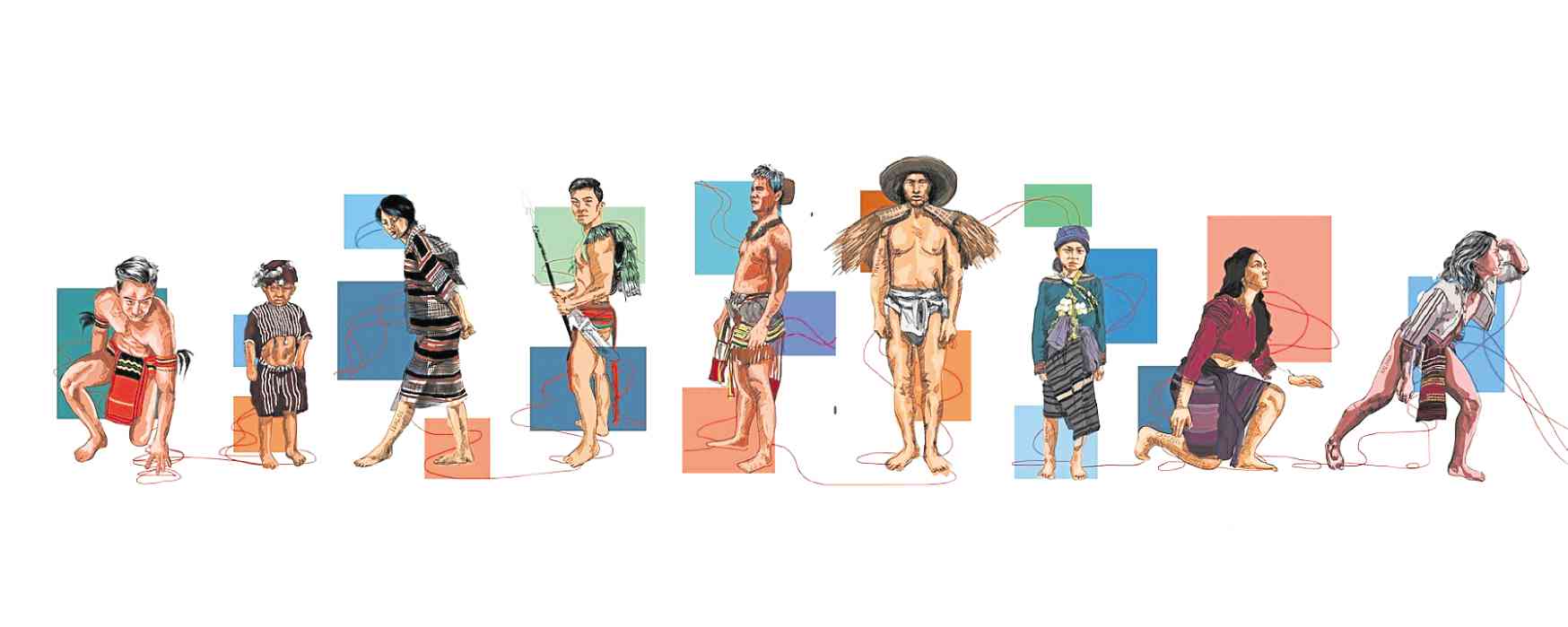

CULTURAL LINK A red string serves to link the identities of Cordillerans painted by Tarlac-born artist Vena Martinez on blank walls in different spots in Baguio City. The images are based on friends she encountered when she took fine arts at the University of the Philippines Baguio. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

BAGUIO CITY — Visitors arriving in this mountain resort city are greeted by figures of a Kankanaey man and an Ibaloi woman in traditional attire painted on the walls outside a bus terminal.

The figures are not just figments of the imagination; they are friends in real life who have a chance encounter with 21-year-old artist Venazir “Vena” Hannah Martinez.

Martinez has been using street art to depict the cultural diversity in Cordillera for almost two years now. Sometimes, she is seen late at night with a spray can and an emergency light to help her bring the murals to life.

Social experiment

“I got tired of the traditional media where you’re just inside a studio. I didn’t want to conform to that so I thought of street art,” she said.

She started her artworks in 2017 as part of a “social experiment” for her thesis at the University of the Philippines Baguio where she took up fine arts.

Her first work — paintings of the traditional Kalinga tattoo called “gayaman,” or centipede — was sprawled all over the streets.

“I vandalized a whole town because I wanted to start a conversation and initiate different visual perceptions. For people to ask: Is this vandalism? But it has cultural relevance,” Martinez said.

“Some were able to recognize that it was the Kalinga tattoo. That it was made by an artist and that one part is connected to the other,” she said, adding that it proved her social experiment worked.

NOT VANDALISM Martinez believes public art is meant to be appreciated by ordinary people. —KRIZZA MAE PACLEB/CONTRIBUTOR

Project Hila-Bana

Now her street art can be seen in public areas, such as a café near Baguio Cathedral and along Session and Military Cutoff roads.

A native of Tarlac province, Martinez was fascinated by the unique indigenous groups in the Cordillera.

“I felt alienated at first so I started to learn about the complexity of the cultures we have. I want to share this with other people who don’t have an idea about these cultures,” she said.

With the urge to widen her scope and to promote indigenous traditions, Martinez’s art soon emerged in various places around the city. This evolved into an advocacy she called “Project Hila-Bana.”

Red string

Hila-Bana was coined from the Filipino terms “hilbana,” or temporary stitching, and “hila,” or pull.

The identity marker of her art is a red string that suggests the connection to different cultures into one identity as Filipinos.

The string is inspired by traditional weaving. But it also signifies loss of cultural identity, hence the “hila” in Hila-Bana, Martinez said.

“Filipinos are so porous that we are slowly forgetting our identity due to external influences,” she said.

She portrayed this in a street art near the Special Education (SPED) Center on Military Cutoff Road.

On the wall is a painting of an Ibaloi girl in full color because the SPED Center uplifts culture as it hones children to appreciate their identity, Martinez said.

“But as the girl moves toward a Chinese-owned establishment, she slowly loses her color. As if the strings are coming off and along the way she forgets who she is. That is the message of Hila-Bana,” she said.

Her works have since become popular, owing to a mural she made near the bus station. Her works also have become favorite spots for tourists who take photos that are shared online.

STREET ART Vena Martinez chose street art to examine the culture and core identity of Cordillera communities. She began experimenting with mural art for her school thesis. —PHOTOS BY VALERIE DAMIAN

Criticisms

The murals were not accepted at first, however. “People … thought it was vandalism,” she said.

Martinez said she had also been criticized by some local artists. “Now that I’ve become a public figure, some called me a sellout,” she said.

She does not charge anything for her murals. She sustains her work and lifestyle by accepting other projects that offer payment.

Martinez said she was just starting to create murals and that she wanted to paint the empty walls in the city with red strings and colorful figures.

“Street art is a very strong medium where everyone has access to it. Not everyone has access to a museum or a gallery, and I want people to see that,” she said.

“So it’s not necessarily just for me. It’s for people to start a conversation and to appreciate that piece of art,” she said.