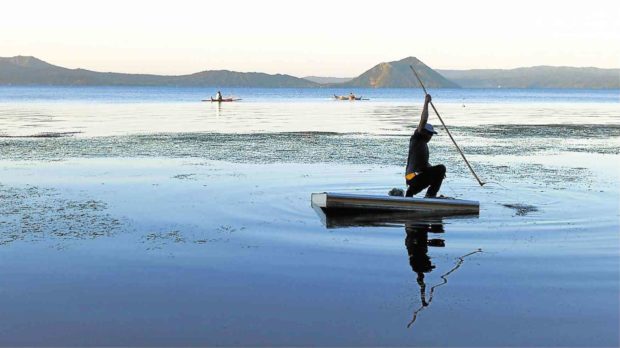

ACTIVE VOLCANO Taal, one of the active volcanos being monitored by government volcanologists in Luzon, provides a serene backdrop to Taal lake, a source of livelihood for fishermen in Batangas. —CLIFFORD NUÑEZ

TANAUAN CITY — The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) is looking at better ways of detecting earthquakes and volcanic activity in the active Taal volcano and caldera.

Last week, the agency unveiled its borehole seismic station, the 13th in the network of seismic monitoring stations in Taal volcano and the first of its kind in the Philippines.

Unlike most seismometers fixed above ground, this one, with the sensor enclosed in a steel cylinder and covered with aluminum oxide sand to keep the moisture off, is buried 20 meters deep.

This minimizes unnecessary noise recorded during ground movements, Phivolcs said.

Western tech

The borehole station was established in December in a farm at Barangay Bilog-bilog here, one of the Taal lakeshore towns and cities in Batangas province.

The station, powered by a 600-watt solar panel, transmits data real time via radio waves and satellite to the Phivolcs observatory in Talisay town and to its headquarters in Quezon City.

The P2.5-million system uses American technology, said Science Undersecretary Renato Solidum Jr., Phivolcs officer in charge.

He said the same seismometer station would also be put up on Mt. Kanlaon on Negros Island province and on Mt. Bulusan in Sorsogon province.

In a briefing, Solidum said the borehole station gave Phivolcs a “larger coverage and higher accuracy” in monitoring Taal’s volcanic activities.

Enough warning

He said the new station could also help detect movements of the West Valley Fault, which experts had warned about triggering a catastrophic earthquake, called the “Big One,” in Metro Manila and nearby provinces.

In Southern Luzon, the West Valley Fault ends in Calamba City in Laguna province.

“If we could detect signs of movements of the fault just before it gives in, we could give people enough warning,” Solidum said.

Tanauan City, which sits on the Taal caldera, was a vital location for the seismic station, he said.

Destructive blasts

The Taal caldera has 40 craters and spans about 25 kilometers in diameter, while the main Taal crater, in the middle of the lake, was responsible for the last four destructive eruptions in 1749, 1754, 1911 and 1965.

The 1754 eruption caused a tremendous amount of ashfall that buried a church and triggered a series of eruptions that lasted for months.

The 1911 and 1965 eruptions caused base surges, or the horizontal flow of pyroclastic materials across the lake and ground, Phivolcs said.

Solidum said an eruption could easily affect 100,000 to 200,000 residents and bring ashfall that could reach Metro Manila and paralyze the operations of Ninoy Aquino International Airport.

“The worst case scenario [is it could affect] even more,” he said.