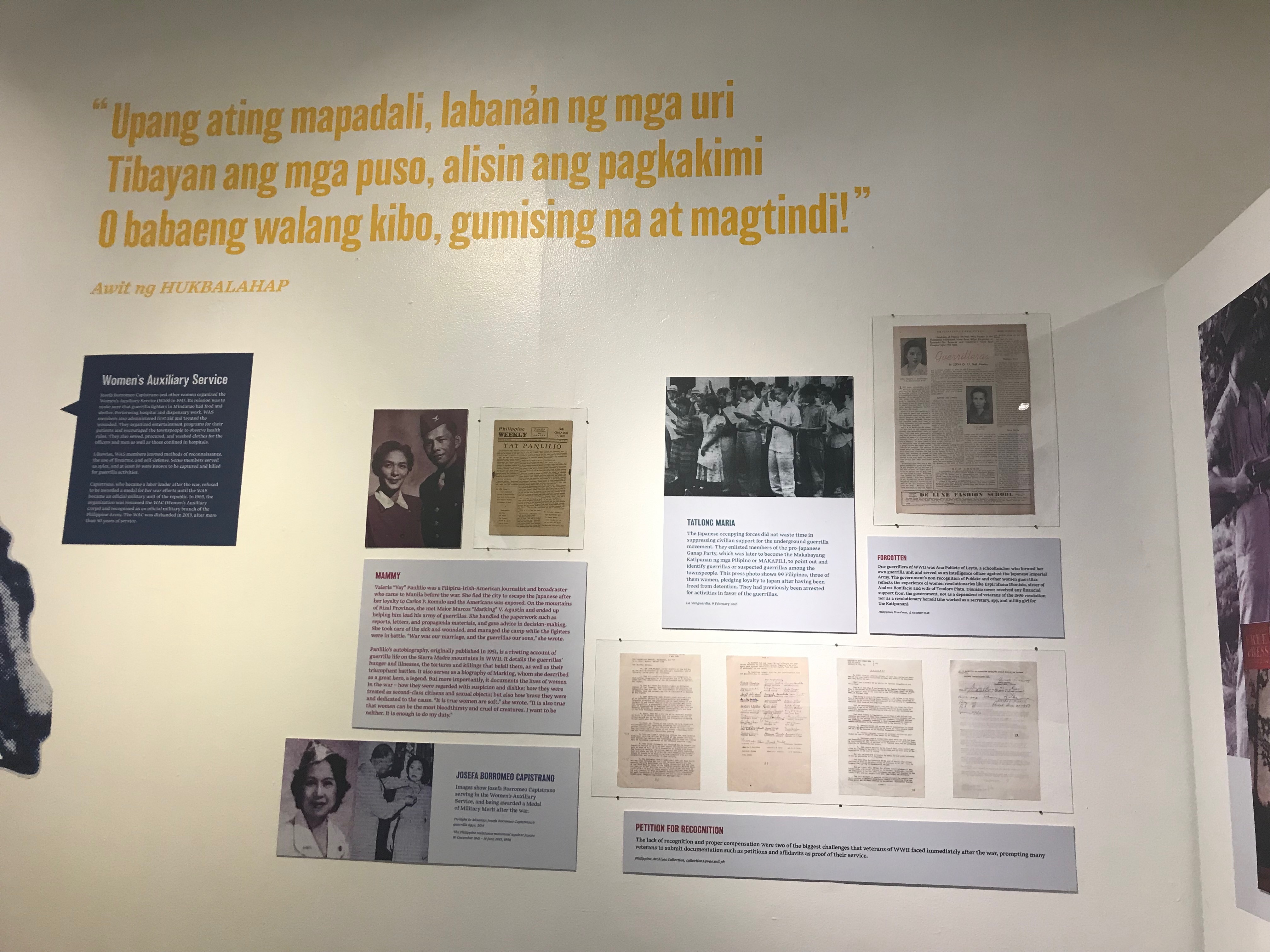

WAR VICTIMS At the ongoing “Women and War” exhibit at Ayala Museum, photographs show how women became victims of atrocities—from being sexual slaves and comfort women to suffering physical assault and violence from Japanese soldiers during World War II. —PHOTOS BY Mariejo S. Ramos

(First of two parts)

For Estelita Dy, 89, memory is precise but brutal.

For example, she remembers how, in 1945, the sound of warplanes hovering above their town in Negros Occidental signaled liberation from the Japanese World War II. But the pain endures as she recalls her past as a “comfort woman” of the Japanese Imperial Army.

“I was running from a Japanese soldier … I was running so fast that I stumbled,” recalls Dy, whom people refer to as Lola (grandmother) Estelita. “The soldier pulled my hair, twisted my arms with a tight grip, and put me in a truck that took us to a [Japanese] garrison.”

For three weeks, Dy was held in the garrison in Talisay as a sex slave, along with thousands of other Filipino women.

She remembers being told by another woman there not to resist: “You will get killed. Just follow their orders, so you won’t get hurt.”

That the memory was harrowingly showed in the way Dy tightly gripped the microphone during the launch of the “Women and War” exhibit on Feb. 2 at Ayala Museum, where her words echoed across a room filled with mementos, books and photographs of Filipino women’s suffering and resilience during World War II.

“What she was feeling then was not anxiety, but rage,” Sharon Cabusao-Silva, executive director of Lila Pilipina, later told the Inquirer. “She was asked once: ‘How did you cope with the pain?’ Lola Estelita said she had filled her daily life with work as a way to forget.”

Victims of war

Forgetting is convenient, but Dy and six other lolas with Lila Pilipina, an organization of former comfort women and advocates, have vowed to continue seeking justice for generations of victims of sexual slavery, war and aggression.

“When we talk about World War II, we always hear about soldiers, men and acts of valor, but women hardly become its focus. Women are always victims of war—of sexual abuse and rape,” said Ricardo Jose, a history professor at the University of the Philippines, who has studied the issue of comfort women.

An estimated 250,000 Asian women were made sex slaves by Japanese soldiers from 1942 to 1945. In the thick of the battle for memory of this period are women who sparked movements in their respective countries, from Southeast Asia to South Korea, Taiwan, China and Australia.

But while the campaign for justice for Filipino comfort women has reached the United Nations, no formal and public apology has been issued by the Japanese government. The women have to contend with perfunctory state support and attempts at historical revisionism, Silva said.

And the women, who numbered 174 when first organized by Lila Pilipina in the early 1990s, are dying due to ill health, old age and poverty.

Contrast: Korea and PH

The global movement, however, has come a long way from its locus in South Korea, a former colony of Japan, where, in 1991, Kim Hak-sun broke her silence of nearly 50 years to testify on how she became a sex slave.

It triggered the call for comfort women in other countries to come out, Silva said.

In the Philippines, investigations confirmed wartime “comfort stations” in certain provinces and cities such as Iloilo, Masbate, Tacloban, Cebu, Baguio, Davao, Cagayan de Oro, Butuan, Laguna, Leyte, Antique (Panay Island), Mindoro, Negros and Cagayan Valley (Isabela).

A document revealing the existence of 19 Filipino comfort women in Iloilo was also found by then Rep. Hideko Ito of Japan’s Diet on March 10, 1992.

Maria Rosa Luna-Henson was the first Filipino to tell her story as a sex slave on Sept. 18, 1992, in Angeles, Pampanga province. Her story boosted the confidence of other women at that time to come forward, with the help of feminist activist Nelia Sancho.

But according to lawyer Virginia Suarez of the women’s group Kaisa Ka, who has been leading the political activities of Malaya Lolas (Free Grandmothers) of Mapaniqui, Pampanga, South Korea’s community and government support for former comfort women offers a sharp contrast to the Philippine situation.

Korea’s case is inspiring because its government is strongly supportive of the cause of the “halmoni” (the Korean term for grandmother). “The people in communities there gather thrice a day just to guard the comfort women statue, so that it won’t be demolished,” Suarez said.

In 1990, South Korea formed the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, a nongovernment organization working for a just resolution of the issue, including restoration of the victims’ human rights domestically and internationally.

The Korean Council, backed by its government, provides welfare programs for survivors—from medical assistance to regular visits, birthday and holiday events, and a free shelter. There are no such services for former comfort women in the Philippines.

30-year protest action

“The halmonis in Seoul have also been staging the world’s longest protest action—the ‘Wednesday demonstration’ in front of the Japanese Embassy—for almost 30 years now,” Silva said.

She recalled how, in one of Lila Pilipina’s visits to South Korea, a halmoni went for a hospital checkup to make sure she would have “enough physical strength to protest in the streets.”

“It’s very different here. We don’t have those medical services, and it’s very difficult for the lolas to even travel now because of their poor health,” she said.

In Pyeonghwa (Peace) Park in Mapo-gu, Seoul, various kinds of flowers bloom for all seasons in a forest dedicated to the halmoni. The first tree in the park was planted by a halmoni as a symbol of reconciliation, healing and peace.

“The Forest in Memory of Girl,” put up in 2015 through a crowdfunding effort of 550 contributors, is only one of many state-sponsored memorials in South Korea to honor the victims of Japanese military sexual slavery.

These structures, according to the “Peace Map” commissioned by the Korean Council, were built for the general public’s reflection “over women’s human rights while following the victim-survivors’ footsteps.”

In Seoul’s residential backstreets, a moving mural depicts the halmoni’s story—from a scared girl fleeing Japanese soldiers to suffering as a comfort woman, and finally being embraced by her kin after liberation.

The Korean Council also houses War and Women’s Human Rights Museum in Mapo-gu, built in 2012 as a place for education and remembrance of violations against women.

Elsewhere in Korea, statues of peace (“sonyeosang”) have been erected “to call for apology and remembrance” and to hope for “prevention of sexual violence in armed conflict across the world,” the Korean Council wrote on its website.

Removal of PH statues

In the Philippines, two comfort woman statues—one put up in December 2017 on Roxas Boulevard in Manila and the other at a private property in San Pedro, Laguna—were both removed last year, on the demand, Silva believes, of the Japanese Embassy.

Lila Pilipina eventually launched the “Flowers for Lolas” campaign to protest against the statues’ removal.

“We wrote public statements, letters, reached out to similarly oriented organizations in other countries,” Silva said. “We acted, and acted alone, because … our own government didn’t support us and in fact was the one who so obediently carried out the removal.”

Why, Suarez mused, are there so many shrines to the kamikaze nationwide yet a statue for victims of military sexual slavery is removed and cannot be built in public places?

“[Protest] is possible in South Korea because of state intervention,” she said. “That makes it easier for people to mobilize because the government stands by their cause—unlike here.”

She added: “Demanding accountability from Japan and recording the history of sexual slavery in the education system need to be initiated by the state.”

Speaking out

“What dignity can there be in a nation that does not honor its grandmothers, particularly those who have become victims in wars and foreign aggression?” Silva asked the audience at the Ayala Museum launch.

But Filipino comfort women now speak out against the structures that made the violence against them possible—and against all wars.

“The role of our lolas today is to promote and propagate historical truths so that there will be some level of awakening among the youth,” Silva said.

Hopefully, she said, they would succeed in preventing more wars of aggression and more women victims of military sexual slavery.