Groups reject lower age of crime responsibility

Rather than focus on locking up youthful offenders, the government should exert more effort to solving the root causes of children’s involvement in criminal activities, according to the Philippine Interfaith Movement Against Human Trafficking (Pimaht).

“Poverty and lack of opportunities to the majority of Filipino families in our country are the very same drivers that breed vulnerability to children to be in conflict with the law,” Pimaht said in a statement.

“We strongly encourage our government to focus its attention on the promotion of the rights and welfare of children, and address the roots of social problems driving children to commit crimes.”

The coalition is composed of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), National Council of Churches in the Philippines, Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches, Philippine Children’s Ministries Network and Talitha Kum-Philippines.

House legislation

Article continues after this advertisementHouse Bill No. 8858, which was passed on third reading on Monday, was intended to amend Republic Act No. 9344, or the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006, to lower the age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 12 years old. Two similar bills are pending in the Senate.

Article continues after this advertisementUnder the House bill, children 12 years or older but under 18 shall not be held criminally liable unless they had acted “with discernment” when they committed the alleged crime.

President Duterte, who was pushing for 9 years old, has said he was “comfortable” with 12.

In a separate statement on Monday, the CBCP warned of “greater harm” to the children if the age was lowered.

“There is no way we can call ourselves a civilized society if we hold children in conflict with the law criminally liable,” the prelates said.

Presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo said the bishops should first study the background and the provisions of the proposed measure.

“It has been there since the 1900s. The Revised Penal Code had that provision. That was only changed in 2006, raised to 15 years old,” he said in a press briefing.

Pimaht said the measure did not make sense as data on crimes committed by children showed that they comprised barely 3 percent of all crimes in the country.

Multiple studies

About 100 alumni of the University of the Philippines’ (UP) School of Economics have submitted a position paper to the House and the Senate expressing deep concern over the proposed law.

They said the House and Senate bills ignored the results of multiple studies on brain and behavioral development that showed that in the “Philippine context,” the age of discernment, which “requires intellectual, psychological and emotional maturity, is between 15 and 18 years old.”

They called the lawmakers’ attention to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which urged states not to lower their minimum age of criminal responsibility to 12. Doing so would be a “serious retrogression,” the alumni said.

They also said the proposed measure would be inconsistent with other laws that recognized constraints on children, ineffective and inefficient in fighting crime, unfair and would go against social norms.

The UP economics alumni said the House and Senate bills “contradict the intent and substance” of other laws and rules in the country which all indicated awareness of the legal constraints on children.

They said, for example, that children below 18 were not allowed to marry, to vote, to buy, sell or smoke tobacco or drink alcohol.

They questioned the effectiveness and efficiency of the plan as a means to discourage children from engaging in criminal activities precisely due to their lack of discernment and full knowledge about laws and consequences of breaking them.

Children also were unaware of the cost of criminal behavior were prone to “risk-taking and novelty-seeking activities” and being easily swayed to follow orders, they added.

“The proposal merely addresses the technique [or the technology] that uses juveniles as accessories to commit crimes,” they said, adding that criminals will just adapt by using children even younger than 12.

They said in addition to poverty, the lack of gainful employment, education and productive opportunities were the main causes of crime committed by children, especially against property.

Sledgehammer to crack nuts

“The predictable outcome of further reducing the minimum age of criminal responsibility is having more children from poor families being detained or imprisoned. A sledgehammer is being used to crack a nut, as it were, considering that the children account for a tiny fraction of total crimes,” the position paper said.

The group also urged legislators not to undermine social norms, which include respect and care for both the elderly and the children.

It said detention in an “impersonal center” or a Bahay Pag-asa with inadequate facilities would push children away from society and likely to turn them into hardened criminals.

The group conceded that the current law has it weaknesses but it was far better than what the legislators were proposing.

Survey backs 15 years old

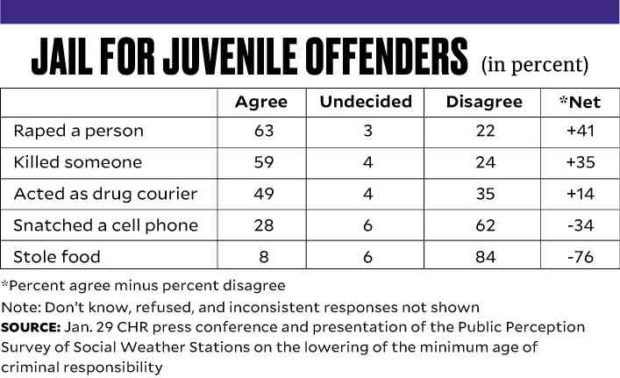

A survey by Social Weather Stations (SWS) and the Commission on Human Rights last year showed that for the majority of Filipinos who think that children who commit crimes should be jailed, 15 years old was the age they believe minors should be held in custody.

The survey said majority of Filipinos agreed to jailing minors for rape (63 percent) and for murder (59 percent). About 49 percent agreed to jail minors who serve as drug couriers.

Only 28 percent agreed to jailing for minors caught stealing a cell phone, and 8 percent said minors who stole food should be jailed.

The survey polled 1,500 adult respondents in Metro Manila from July 13 to 16, 2018, and from Dec. 18 to 22 in the rest of the country. —WITH REPORTS FROM JULIE M. AURELIO AND PATRICIA DENISE M. CHIU