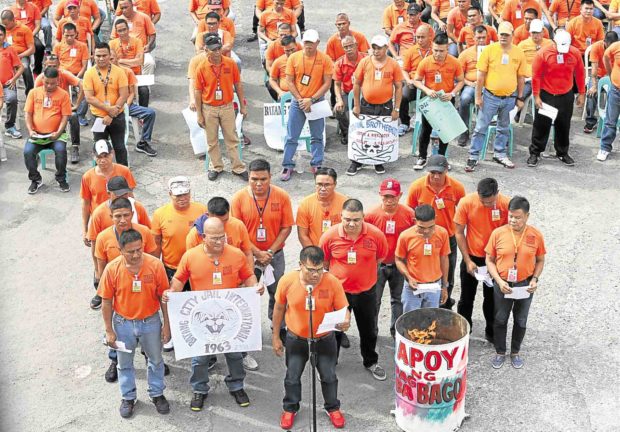

NO MORE GANGS Leaders and members of Batang City Jail, one of the 12 gangs at the maximum security compound in New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City, burn their group’s insignia in front of Bureau of Corrections officials. The move is part of BuCor’s efforts to get rid of the gang system which has thrived in the national penitentiary for decades. —MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

Over 17,000 or more than 64 percent of the 26,930 inmates at New Bilibid Prison (NBP) have agreed to renounce their gang affiliations, a step that the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) hopes will help dismantle the gang system that has thrived in the national penitentiary for decades.

The leaders of all 12 gangs at the maximum security compound signed on Thursday an agreement with a litany of pledges—including the abolition of the very groups they led—in a spectacle-laden ceremony that featured the burning of posters emblazoned with each gang’s insignia.

According to BuCor data, only 2,307 of the compound’s 19,653 inmates were considered “querna,” as prisoners refer to those who do not belong to any gang.

The three biggest groups are Sputnik (4,474 members), Genuine Ilocano Group (2,887) and Batang City Jail (2,326).

BuCor chief, Director General Nicanor Faeldon, said in a press conference that dormitories would now also be mixed, marking an end to the longstanding practice of assigning inmates to cells based on their gang membership.

“There’s no family that is happy when its head joins a gang,” Faeldon said. “We are taking away their macho mentality here.”

The compound hosts the highest number of inmates at NBP. The medium security compound has around 5,500 prisoners compared to 650 for the minimum security compound. There are also plans to make the two compounds gang-free at some point as well.

The intricate links that have been cultivated among gang members over the decades, however, may take more than a signed contract to disentangle.

Vital social structure

Gangs have endured at both NBP and the correctional system at large due to their ability to act as a vital social structure, providing members with protection, financial support and a semblance of family in jails and prisons bedeviled by notoriously nightmarish conditions.

The informal system of self-governance among gangs, a vestige of the American colonial era, has also been proved integral to peacekeeping in overcrowded, understaffed facilities.

Faeldon, however, claimed that multiple dialogues held with gang leaders about the abolition of their groups had been met with little resistance, and that he succeeded in getting them to take ownership of the move as if it were their own idea.

“There’s stigma in joining a gang. We tried to show them the government would still embrace them,” he said. “Start treating them like human beings so they will start acting like human beings.”

The endgame for the BuCor chief, however, is the eradication of criminal gangs outside the national penitentiary. He said he expected the newly unaffiliated inmates to influence their former gangmates to stop their illegal activities and relinquish their affiliations.

“The inmates will lead the nationwide abolition of gangs, including those on the streets,” Faeldon said.

During the ceremony, he told prisoners: “Due to your leadership, even outside the prison, we will stop syndicated crime.”

Limited influence

But Alias Aldrin, leader of Sputnik and an NBP inmate since 2007, told reporters that while he held sway over his members inside the compound, he had limited power over “outsiders.”

Both he and alias Bugoy, the leader of rival gang OXO, said they were fine with the merging of different gang members inside the prison dorms.

“We’re now one big family,” Aldrin said.

Asked what they hoped to get in return for their cooperation with BuCor, the leaders had just two wishes—more time to be allotted for visits and lights that actually worked at night. The elderly prisoners could not find their way to the toilet after dark, Bugoy said.