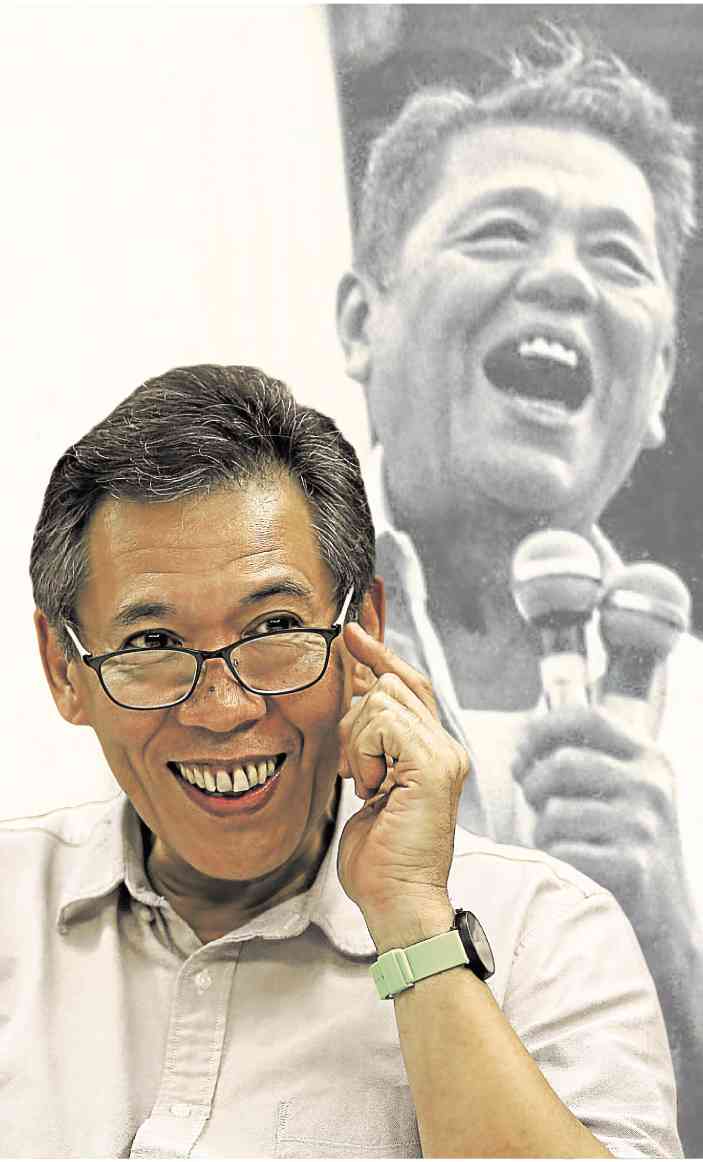

FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS Human rights lawyer Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno (foreground in this composite photo) tells the Inquirer that his father, the late Sen. Jose “Pepe” Diokno, has been his lifelong inspiration in making his own contribution as a champion for justice as he runs for the Senate. – EDWIN BACASMAS/DIOKNO FOUNDATION

Whether in the courtroom or in the classroom, Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno, 57, bears the full historical weight of his father’s name: a rallying symbol for human rights under the Marcos regime.

But Chel, whose baritone voice elucidates rather than exhorts, never thought he would ever run for senator.

His father, the late Jose “Pepe” Diokno, often cited as the country’s best senator — a tub-thumping, fiery orator who famously said Ferdinand Marcos could not sit for long on a throne of bayonets.

“I cannot ever say I was ever like that,” the mild-mannered lawyer and academician told the Inquirer. “We’re polar opposites in many ways.”

Then Rodrigo Duterte, the tough-talking Davao City mayor who idolizes Marcos, became President.

And as the nightly body count in the drug war soared and vocal critics were silenced, Diokno — who was 13 when Marcos declared martial rule in 1972 — recognized the portents of a rising dictatorship.

Had this been “an ordinary time,” Diokno said, “and there was no ongoing assault on our democratic institutions, I would not bother (running).”

‘Mouth of the abyss’

“But let’s put it this way: We are looking straight into the mouth of the abyss,” he said.

Now the son of one of Marcos’ foremost political prisoners is jockeying for a Senate seat against the dictator’s daughter, Imee. Set in the age of disinformation, their campaigns will test how well Filipinos remember and learn from their history.

The President’s term is a refresher course on how Marcos governed: by fear and fist, according to Diokno.

“The tactics were a bit different in that (human rights violations) were blatant under martial law. Now you have an outwardly democratic government, right to freedom of speech, right to life. But go deeper and you notice that in many ways these rights are becoming more illusory,” he said.

Like his father 55 years ago, Diokno was drawn to the opposition to check the whims of a populist. He is on the Liberal Party slate, although he is not a party member.

Co-opted courts

But the past forays into politics of the founding dean of De La Salle University’s College of Law had often been set against the backdrop of court battles. He has never held a government post apart from serving as special counsel in previous Congresses.

The veteran human rights lawyer laments what he sees as courts being co-opted by the Duterte administration.

According to Diokno, the volley of attacks against the judiciary “immediately destroyed their independence”—from the first “narcolist” in 2016 tagging a dead judge to the drug trade, to the quo warranto petition that ousted former Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno.

It’s what has pushed the political neophyte to run for a seat in a Senate, hopefully the last brake to an emerging autocrat. “I could fight a hundred million cases in court, but is that going to do any good?” he asked. “I don’t think so.”

The court triumphs of the chair of the Marcos-era Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) were no small feats, either. In 2017, he challenged before the Supreme Court the constitutionality of “Oplan Tokhang,” the brainchild of former Philippine National Police chief and now senatorial aspirant Ronald dela Rosa.

As a result, the Supreme Court compelled the PNP to release all spot reports on all police operations under the drug war, estimated to have killed around 25,000 people since 2016.

Outside ‘Magic 12’

But despite his name and stellar track record, Diokno ranks well outside the “Magic 12” among the senatorial aspirants.

“It’s an uphill climb,” he said. It’s why he’s banking on a narrative the middle-class Diokno family shares with the rest of the country: injustice.

As he guns for the Senate, the self-styled “boses ng katarungan” (voice of justice) is keenest on reforming the country’s justice system.

A lot of injustices, he said, are rooted in the politicization of the judiciary where judges are beholden to their backers.

It’s also woefully neglected: only 2 percent of the national budget goes to the judiciary, while a third of all posts for judges and prosecutors nationwide remain vacant.

Diokno also cited the “judicial impunity” cloaking the courts: the Office of the Ombudsman, for example, cannot investigate any member of the judiciary unless the Supreme Court has first investigated him or her.

An old Supreme Court ruling also exempts justices from the mandatory release of their statements of assets, liabilities and net worth as required by Republic Act No. 6713.

This “malfunctioning” justice system, he said, is what enables criminals to get away even with stealing billions of taxpayers’ money—a swipe at former first lady Imelda Marcos, who was convicted of graft after 27 years.

Life-or-death situations

On the ground, these abstraction translates into life-or-death situations for the poor, ironically Mr. Duterte’s most solid base.

Every Filipino has felt the harsher economic conditions and the systematic killings of drug suspects, he said, but “the poor most of all.”

“When you’re mistreated, when you’re treated by the government as being less than a person, you feel that,” he said. “It’s impossible to be poor and not feel that.”

The challenge, he said, is how to put these gut issues into words that do not utilize populist rhetoric, which Marcos and Mr. Duterte both successfully weaponized to create divisions.

“We need to speak truth to power. There is no other way. The only way to break through the crust of lies and of violence is to talk about the truth,” he said.

It’s something his father, Diokno’s greatest inspiration, would have said. Ka Pepe’s lifelong fight against dictatorship had shaped Diokno’s worldview, which remains unshaken amid present attempts to demonize human rights advocates.

His greatest challenge, however, is to project a greater measure of himself and step outside the shadow of his father.

First, the academician has to learn the ropes of the campaign trade.

“I’m learning how to sing, at least,” he laughed. “But it’s not characteristic for me to simplify issues so much. There is no shortcut to justice.”