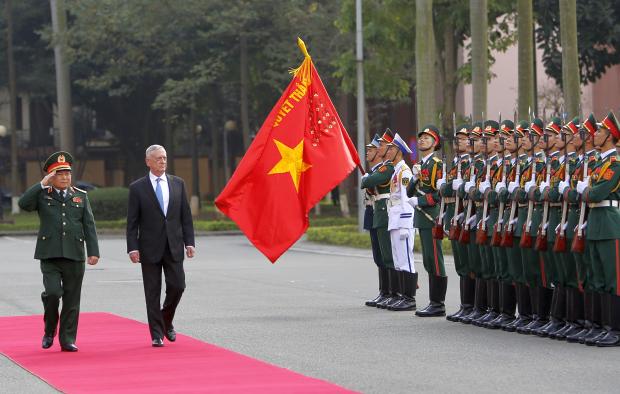

In this photo, taken Jan. 25, 2018, U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and his Vietnamese counterpart Ngo Xuan Lich, left, review an honor guard in Hanoi, Vietnam. By making a rare second trip this year to Vietnam, Mattis is showing how intensively the Trump administration is trying to counter China’s military assertiveness by cozying up to smaller nations in the region who share American wariness about Chinese intentions. (Photo by TRAN VAN MINH / AP)

WASHINGTON — By making a rare second trip this year to Vietnam, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis is signaling how intensively the Trump administration is trying to counter China’s military assertiveness by cozying up to smaller nations in the region that share American wariness about Chinese intentions.

The visit beginning Tuesday also shows how far U.S.-Vietnamese relations have advanced since the tumultuous years of the Vietnam War.

Mattis, a retired general who entered the Marine Corps during Vietnam but did not serve there, visited Hanoi in January.

By coincidence, that stop came just days before the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Tet was a turning point when North Vietnamese fighters attacked an array of key objectives in the South, surprising Washington and feeding anti-war sentiment even though the North’s offensive turned out to be a tactical military failure.

Three months after the Mattis visit, an U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, the USS Carl Vinson, made a port call at Da Nang. It was the first such visit since the war and a reminder to China that the U.S. is intent on strengthening partnerships in the region as a counterweight to China’s growing military might.

The most vivid expression of Chinese assertiveness is its transformation of contested islets and other features in the South China Sea into strategic military outposts.

The Trump administration has sharply criticized China for deploying surface-to-air missiles and other weapons on some of these outposts. In June, Mattis said the placement of these weapons is “tied directly to military use for the purposes of intimidation and coercion.”

This time Mattis is visiting Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s most populous city and its economic center. Known as Saigon during the period before the communists took over the Republic of South Vietnam in 1975, the city was renamed for the man who led the Vietnamese nationalist movement.

Mattis also plans to visit a Vietnamese air base, Bien Hoa, a major air station for American forces during the war, and meet with the defense minister, Ngo Xuan Lich.

The visit comes amid a leadership transition after the death in September of Vietnam’s president, Tran Dai Quang. Earlier this month, Vietnam’s ruling Communist Party nominated its general secretary, Nguyen Phu Trong, for the additional post of president. He is expected to be approved by the National Assembly.

Although Vietnam has become a common destination for American secretaries of defense, two visits in one year is unusual, and Ho Chi Minh City is rarely on the itinerary.

The last Pentagon chief to visit Ho Chi Minh City was William Cohen in the year 2000; he was the first U.S. defense secretary to visit Vietnam since the war. Formal diplomatic relations were restored in 1995 and the U.S. lifted its war-era arms embargo in 2016.

The Mattis trip originally was to include a visit to Beijing, but that stop was canceled amid rising tensions over trade and defense issues. China recently rejected a request for a Hong Kong port visit by an American warship, and last summer Mattis disinvited China from a major maritime exercise in the Pacific.

China in September scrapped a Pentagon visit by its navy chief and demanded that Washington cancel an arms sale to Taiwan.

These tensions have served to accentuate the potential for a stronger U.S. partnership with Vietnam.

Josh Kurlantzick, a senior fellow and Asia specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an interview that Vietnam in recent years has shifted from a foreign and defense policy that carefully balanced relations with China and the United States to one that shades in the direction of Washington.

“I do see Vietnam very much aligned with some of Trump’s policies,” he said, referring to what the administration calls its “free and open Indo-Pacific strategy.” It emphasizes ensuring all countries in the region are free from coercion and keeping sea lanes, especially the contested South China Sea, open for international trade.

“Vietnam, leaving aside Singapore, is the country the most skeptical of China’s Southeast Asia policy and makes the most natural partner for the U.S.,” Kurlantzick said.

Vietnam’s proximity to the South China Sea makes it an important player in disputes with China over territorial claims to islets, shoals and other small land formations in the sea. Vietnam also fought a border war with China in 1979.

Traditionally wary of its huge northern neighbor, Vietnam shares China’s system of single-party rule. Vietnam has increasingly cracked down on dissidents and corruption, with scores of high-ranking officials and executives jailed since 2016 on Trong’s watch.

Sweeping economic changes over the past 30 years have opened Vietnam to foreign investment and trade, and made it one of fastest growing economies in Southeast Asia. But the Communist Party tolerates no challenge to its one-party rule. Even so, the Trump administration has made a focused effort to draw closer to Vietnam.

When he left Hanoi in January, Mattis said his visit made clear that Americans and Vietnamese have shared interests that in some cases predate the dark period of the Vietnam War.

“Neither of us liked being colonized,” he said. /atm