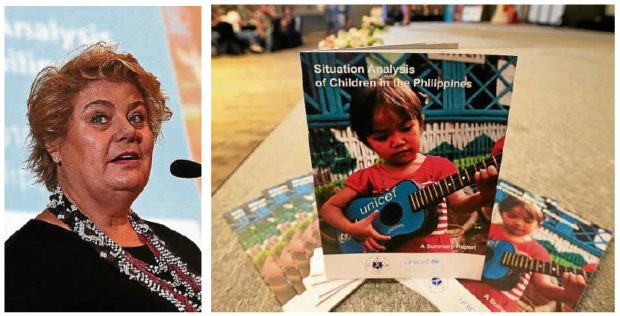

UNICEF REPORT Lotta Sylwander (left), Philippine representative of the United Nations Children’s Fund, says the agency’s research study (right) aims to shed light on the progress to protect children’s rights across the country. —PHOTOS BY GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

Child rights advocates on Tuesday raised concerns over the growing number of minors being killed in President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, one of the “worrying” situations of children in the Philippines who were being subjected to various forms of violence.

Lotta Sylwander, country representative of the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) said it was “not acceptable” that children were getting killed, either directly or accidentally, in the campaign against illegal drugs and in other conflicts.

“We believe that children always should have a second chance, so subjecting them to that kind of violence is really not fair, and these are the forms of violence that we really object to and find not acceptable,” Sylwander said.

By Unicef’s latest unofficial count, 35 children had been “either directly or accidentally” killed in the government’s war on drugs.

‘Situational analysis’

The UN official made the statement as the agency and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) released on Tuesday a “situational analysis” of children in the Philippines to shed light on the progress the country had achieved toward upholding children’s rights.

According to Assistant Secretary Glenda Relova, the DSWD has partnered with the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), the main agency tasked with the government’s antidrug campaign, to come up with measures to avoid “accidental deaths” of minors.

“This antidrug program is very laudable but admittedly there are gaps in the program that are beyond the control of the leaders [of the implementing agencies],” Relova said.

The Unicef report details what the Philippines has achieved in providing children the services they need for health, nutrition, education, as well as social protection.

While the government has demonstrated a “strong commitment” to improve the situation of children in the Philippines, many girls and boys “continue to face barriers to the full realization of their rights,” the Unicef report said.

National baseline study

“To date, strong economic growth and a comprehensive legal and policy framework have sadly failed to translate into improved outcomes for children across the country,” it said.

Citing the findings of the 2015 National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children by Unicef and the Council for the Welfare of Children, the Unicef report said youths aged 13 to 24 experienced “high” levels of physical, psychological, sexual and peer violence.

About 12 percent of Filipino children aged 13 to 17 are affected by “collective violence,” including the deliberate destruction of their homes, or being witnesses to people being shot, bombs exploding, fighting and rioting, the report said.

The study documented “grave violations” against children in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), including rape, abduction, attacks on hospitals and schools and being used as soldiers.

Citing data from the Philippine Statistics Authority, the report said about 31.4 percent of Filipino children lived below the poverty line, but the number was significantly higher at 63.1 percent in ARMM.

Teen pregnancies

The report also noted the rising rates of teen pregnancies—an average of about 60 births per 1,000 Filipino girls aged 15 to 19.

An estimated 2.85 million Filipino children aged 5 to 15 are out of school, the Unicef report added.

The Unicef and DSWD also were one in opposing proposals to amend the Juvenile Welfare Act to lower the age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 13.

“The Philippines has one of the most solid acts on juvenile justice in the region, which had been researched thoroughly before it was laid on the table. This proposal to lower the age is, for us, a giant leap backwards,” Sylwander said.

Criminal justice system

To bring children into the criminal justice system will “damage the child forever” as the current state of Philippine prisons do not ensure reformation for child offenders, she said.

“Proponents seem to have forgotten that very often adults bring these children into committing crimes. So why are we not doing something about those criminals?” she said.

Relova said the government only needed to enhance an assessment tool it had devised to determine the criminal liability of child offenders, and did not need to lower the criminal age.

“We stand with the position of not lowering the age until a study is presented, based on scientific observation and research, that offenders below 18 years old can act with discernment,” she said.