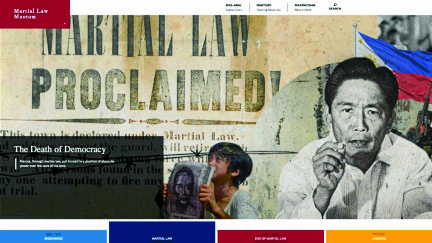

INTERFACE WITH HISTORY A video of President Marcos declaringmartial law in 1972 is one of the many images that people can access at the interactivewebsite of Ateneo de Manila University’s virtual museum. —SCREENGRAB FROM WWW.MARTIALLAWMUSEUM.PH

Joy Jopson spoke about the death of her husband, the martial-law-era student activist Edgar “Edjop” Jopson, in a matter-of-fact tone that could only be the result of decades of coming to terms with his cold-blooded killing.

“There were five bullets in his upper torso and his right thigh was mangled,” Jopson said. “And his legs and feet [were] brutally . . . .” She paused. “They really tried to make sure that he could never stand again.”

Edjop, whom dictator Ferdinand Marcos had once famously dismissed as a “grocer’s son,” was captured in a military raid in Davao City in September 1982. He was taken alive, but according to his widow, fellow detainees overheard camp officials being given a crisp, clear command from Manila: “He was better dead than alive,” she said.

Today Edjop’s legacy is enshrined in a virtual “museum” his alma mater created in his memory and that of the other heroes of martial law, both the prominent and the nameless.

The museum, an interactive website called MartialLawMuseum (martiallawmuseum.ph) or MLM, is the response of Ateneo de Manila University (AdMU) to efforts to whitewash the ruthless era. Launched in September 2017, it has in its first year redefined what a museum can be—and precisely what it means to teach martial law.

Its primary thrust is to educate the youth on the evils of authoritarianism in order to prevent a repetition of the mistakes of the past. It’s a goal shared by the Memorial Commission (MC) created by Republic Act No. 10368, which is tasked with remembering the victims of human rights violations during the Marcos regime.

Ironically, the AdMU-led museum was unable to get backing from a key MC member, the Commission on Higher Education (CHEd): A P6-million grant to operate and maintain the museum previously promised to the university has been rescinded on a technicality.

While the grant itself is not part of the MC’s mandate, the situation illustrates the dearth of available state support to institutionalize how it was during the 14-year military rule.

Community initiative

The creation of MLM was triggered in part by the vice presidential bid of the dictator’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., in 2016, said Arjan Aguirre, a political science professor and the museum’s administrator.

What initially started as a rejection of Marcos Jr.’s candidacy quickly morphed into a community initiative to collect and preserve the narratives of martial law in an online repository.

“History has become hollow because it’s too anchored on facts,” said Aguirre. “But facts by themselves can never be truthful. [There] also needs to be emotion to complement the facts [to] arrive at the truth.”

A virtual museum gives new face to discussions on the Marcos era while democratizing access to information, according to Aguirre. It’s one of the many scattered efforts to counter attempts at distorting history in the absence of a state-backed martial law memorial. (Such a memorial is now slated to be built at the University of the Philippines Diliman.)

With a 20-strong team of researchers and staff and dozens of institutions behind it, the online museum now showcases eye-popping and interactive exhibits on the what and who of martial law, centered on the three tenets of “Mag-aral, Magturo, Manindigan.” Study, teach and make a stand.

The project is internally funded and costs at least P1 million yearly, including expenses for researchers, staff and the servers that host the website, Aguirre said.

What makes MLM unique is its modules for K-12 teachers, which they can use as a guide to integrate martial law information in their lessons.

Mathematics teachers, for example, can use poverty rates or annual state budgets under the Marcos regime to teach Grades 4-6 students how to read and interpret graphs and tables. Seventh-graders up to junior high students, meanwhile, can learn how to use Microsoft Excel to create databases using martial law data.

Salikha grant

Its strong push to educate the youth qualified the project under the CHEd’s Salikha grant, which was established under then Commissioner Patricia Licuanan in 2017.

Launched in partnership with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the grant provides financial support of up to P10 million for creative proposals that would improve pedagogy and learning in the arts, culture, humanities and social sciences.

The AdMU/MLM applied for the grant in November and was told it was approved for P6-million funding in the next month.

Such an amount, Aguirre said, would have lasted the institution three years. It would have meant, among others, the digitization of certain martial-law-era works and images, as well as servers to help the website run faster.

Licuanan, an appointee of President Benigno S. Aquino III, resigned last January amid questions on her numerous foreign trips. She was replaced that same month by Prospero de Vera, who then refused to acknowledge the grant. De Vera did not respond to the Inquirer’s multiple requests for comment. Yesterday, he said through a CHEd official, he could not accommodate an interview on the matter.

Uphill struggle

Corrinah Olazo, head of the NCCA Cultural Dissemination Section that handles Salikha, also said she could not comment on the state of the AdMU/MLM grant as both the decision to approve projects and release funding were “solely up to CHEd.”

It has since been an uphill struggle to keep MLM afloat as it has exhausted much of its budget from AdMU, Aguirre lamented.

“It’s a communal endeavor but we are hard-up on resources,” he said.

The financial strain is even more significant because it is the universities that have primarily taken the initiative to institutionalize the memory of martial law in education materials.

“The social studies books discuss martial law in passing only,” observed Joy Jopson. “They do not truly describe what happened.”

If the funding of MLM is drained entirely, it would leave a fatal hole in efforts to address the absence of a comprehensive curriculum on martial law—an absence that is said to have resulted from the inaction of CHEd and the Department on Education.

Constant reimagining

Universities, as hubs for both teaching and research, are uniquely poised to fill this gap as institutions that not only inform students on what happened but also subject these learnings to constant reimagining, Aguirre said. He said he was envisioning MLM as ultimately being a “center on martial law studies” that could provide subsidies for related research.

“A university should also be a means by which people can discover new things about martial law,” he said.

It’s on university grounds that many of the icons of the era, Edjop included, first felt the stirrings of political activism that would eventually thrust them into the national spotlight.

The Jopsons’ marriage, which lasted less than 10 years before his death on Sept. 20, 1982, was a union between two former student council officials, he in AdMU and she in St. Theresa’s College.

The onus of discussing that dark period should not fall on learning institutions alone, Aguirre said. It should be a “national conversation . . . not just [between] one generation, or activists, or opposition politicians during Marcos’ time. It should be that of the ordinary Filipino.”

But this national conversation should treat martial law as a “recurring issue” that needs to be internalized, not memorized. After all, mere months after MLM’s inception, Congress voted overwhelmingly to extend martial law in Mindanao.

“We keep looking back,” Aguirre said. “But we can look forward, too.”

The museum does this, with entire exhibits dedicated to “spotting the dictator,” forging peace, and expounding on the excesses of the Marcoses and their cronies, who remain politically active.

Perhaps most poignant, however, is its profiles on martial law martyrs. Its citation on Edjop, interspersed by black-and-white photos of him, reads: “To this day, Edjop remains a symbol for the idealistic Filipino youth, dedicating their entire lives to their country and their people, even to the point of death.”