‘No-el’ imposed in Marawi

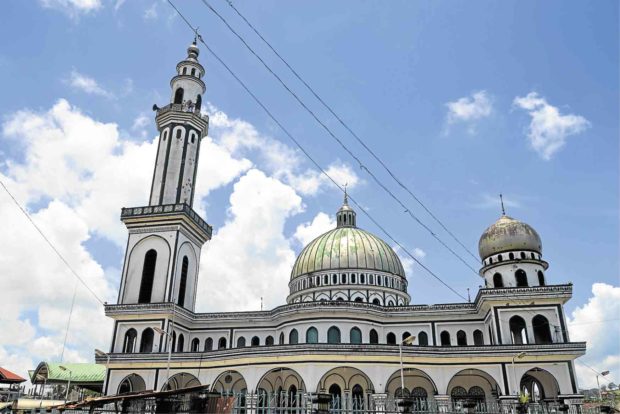

Marawi residents are eager to return to their routines, including prayers at Saduc Grand Mosque. —DIVINA SUSON

ILIGAN CITY—While the country goes to the polls on May 14 to elect village and youth council officials, Marawi City would be waiting for who gets appointed as their village and youth council leaders or settle for incumbent officials.

The city, wrecked by the war on Islamic State (IS) that lasted for five months, would not have elections until security officials decided it was safe.

This sent some residents complaining that after losing valuables, livelihood and property during the war, one of their most basic rights would be gone, too—the right to suffrage.

Yasmin Hadji Aziz, 34, a single mother, said while she had no complaint against officials of her village of Bangon, it would have been better if elections were held.

Aziz was among more than 75,000 villagers allowed to return to their homes in the 72 villages that didn’t become battleground between government soldiers and members of Maute and Abu Sayyaf who had sworn allegiance to IS.

Political right

Aziz said she felt sad because “we cannot exercise our right to suffrage.”

She said if the government would appoint village officials instead, she wished those who would do their jobs well would be appointed.

Jamalodin Mohammad, 37, resident of Panggao Saduc village, said “elections are a political right.”

“Without it, our village officials would be in holdover capacity,” Mohammad said in a phone interview.

“The people could not exercise their right to choose their leaders,” he said.

Elections, he said, serve as “audit time” for officials. “The people would know what they have done,” he added.

“I am not content with the way our barangay officials performed,” he said.

Military assessment

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) said there would be no elections in Marawi City on May 14 because security forces had not recommended it.

Ray Sumalipao, Comelec director in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), said he was not even sure when the elections would be held in Marawi.

The postponement of elections in Marawi, Sumalipao said, “was based on military assessment.”

Sumalipao said despite the liberation of Marawi from IS followers, the military did not recommend elections in all of the city’s 96 villages.

All villages in Marawi, except for 24 that were in ground zero, had been repopulated.

The last time village elections were held in Marawi, which has around 71,000 voters, was October 2013.

Violation

Drieza Lininding, chair of the Marawi-based Moro Consensus Group, said elections should not have been postponed in the entire city.

Postponing elections in some parts of the city “may be justified” but not suspending elections in the whole of Marawi, Lininding said.

She said some residents, including her, saw the suspension of elections as a way to force incumbent village officials to toe the line on what the government wanted to do in Marawi.

Jerome Aba, chair of the group Suara Bangsamoro, said martial law in Mindanao had led to rights violations.

“Because of martial law, the right to suffrage of the people, which is part of their sovereign power, has been violated,” Aba said.

Gov. Mujiv Hataman, of ARMM, said he supported the postponement of elections in Marawi.

“It is not wise to have elections at this time after what happened in Marawi,” Hataman said.

“What they need is to strengthen their unity,” he said.

“The barangay election can be so divisive,” he added. —REPORTS FROM RICHEL UMEL, DIVINA SUSON AND JIGGER JERUSALEM