Salve’s life: A strong case for RH bill

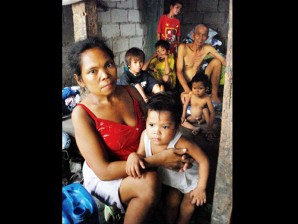

SALVE Paa does not know what the RH bill is, but she admits that her family is suffering financially, primarily because she has too many children. LESTER CAYABYAB/CONTRIBUTOR

MANILA, Philippines—In a tiny house at a resettlement area in Valenzuela City, a woman recounts a scene: watching her eight children devour half a kilo of rice among themselves.

Pregnant again, 37-year-old Salve Paa says she is just as hungry. But she tells herself that a mother must make sacrifices, and waits for her turn to eat.

Minutes later, one of the boys starts to cry, a little finger pointing at the empty plate before him.

The scene, though seemingly surreal, is typical in Salve’s life. Until recently, she has not heard of family planning and has no idea of the reproductive health (RH) bill, and admits that having so many mouths to feed has made such an episode a general norm.

It’s something she laments, especially because she and Alfredo Francisco, her partner of 22 years, do not make much. (Alfredo, 64, has a first family from whom he is separated.)

Article continues after this advertisement“It’s difficult. The little that we earn just goes to food and other expenses in the house,” Salve tells the Inquirer in an interview at Northville, where families dislocated by the North Rail project were resettled by the city government.

Article continues after this advertisementP5,200 a month

Salve works in a plastics factory (but she is temporarily off the grind because she is due to deliver another child this month).

She is paid based on her output: On good days, she earns P1,500; on bad, P700. Alfredo earns P150 a day selling cotton candy.

In all, they take home an estimated P5,200 in a month.

“But minus the expenses, we can barely make ends meet. We can hardly complete three square meals a day,” Salve says.

She details the monthly expenses as: P200 for the house, P200 for electricity, P300 on the average for water, “which is only retailed to us,” and food for 10 people, among others.

As a result, a regular breakfast for the family consists of rice porridge (lugaw) bought at P3 a cup. Small galunggong, the so-called poor man’s fish, bought at P20 a handful, are “delicacies.”

“If there is enough, we have bread for breakfast, but that is very rare,” Salve says.

Because of the money constraints, not one of the 37-year-old’s children has been able to finish his or her studies.

Ana Liza, 21, managed to complete the sixth grade—the highest educational attainment in the family. She is married but often visits.

Her brothers—Aries, 15, and Albert, 12—reached the first grade and prep school, respectively.

Throw ’em out

“We can’t afford to send the children to school,” Salve says. “It’s already a struggle to put food on the table for them every day.”

Then there’s the space problem.

The family lives in a 32-square-meter enclosed space with two tables and a makeshift wooden bed. A hole in the ground serves as the toilet.

The windows consist of square holes covered with leatherette.

During the rainy season, the water easily seeps through the concrete walls and onto the floor, Salve says.

In the summer, the sun’s rays easily heat up the structure. “The roof has not been fixed,” she explains.

At night, Salve has a hard time making the children fit on the “bed.” She says she manages to squeeze herself in, and shows the Inquirer how it’s done.

Alfredo sleeps on the floor.

The situation has moved Salve to throw out two of her elder sons—Alvin and Alfred—several times in the past.

She says that with the two fending for themselves, she figured that she could concentrate on feeding and caring for the rest who cannot as yet survive alone in the world.

Take Angelito, the sickly 3-year-old who has been in and out of the hospital in recent months. The bills for his blood transfusions alone have amounted to some P16,000, Salve says.

“When he becomes ill, I take him to the National Children’s Hospital on España. They care for Angelito there, free of charge,” she says.

But despite having been driven away repeatedly, Alvin and Alfred always came back, and Salve took them in with open arms. After all, she says, she is still their mother.

12, actually

The family should have been much bigger because Salve has given birth to 12 of Alfredo’s children.

Christian and Trisha, then 4 and 7 years old, respectively, died in 2006, followed a year later by Sarah Fe, then 10. Doctors said the three died of sepsis, or the invasion of the body by pathogenic microorganisms.

In 2008, Alvin was accidentally run over by a bus in La Union. Salve lamented the loss of her son, also because the then 18-year-old, who worked as a truck helper, was a big financial help to the family.

Salve admits that her family experiences financial difficulties primarily because she has too many children.

It was only when she was 26 that she learned out about artificial contraceptives. But by then, she had already borne eight children.

In an effort to lessen the number of mouths they were obligated to feed, she and her partner also tried abstinence. But the attempt did not work.

“At one point, I slept at the factory just so I could get away from Alfredo. But he followed me there,” Salve recalls with a chuckle.

Planning a family

Salve does not know what the RH bill is, or what it stands for. But when asked, she says that she is not opposed to sex education.

Had she known about the importance of family planning much earlier, she would not have allowed herself to get pregnant so many times, she says.

This view is in line with some of the provisions of the measure that proposes the integration of sexual awareness in school curriculums and offers couples an informed choice in ways to plan their families.

The proposed legislation is being debated upon in the plenary in the House of Representatives. If passed, it will be sent to the Senate, which can choose to adopt it or pass another version of it.

President Benigno Aquino IIi himself has expressed support for the RH bill. But the Catholic Church and a number of lawmakers remain firmly opposed to the measure and have vowed to block its passage.

Late awareness

“If we had fewer children, then we won’t have most of our financial problems,” Salve muses.

She says that in her community, large families are the trend because some, if not most, of her neighbors do not become aware of family planning methods until much later.

She cites as an example her elder sister who, in her 40s, has seven children.

Salve says that like herself, her sister has to carry on her shoulders the responsibility of feeding too many kids with very little income.

“If you don’t have much money, having too many children is too stressful,” she says. “You’re always thinking of ways to get them through the day.”

Because of her newfound knowledge, Salve plans to undergo tubal ligation to avoid getting pregnant again.

Her ninth (or 13th) child is due, but she says she cannot even think of celebrating. “Our earnings are better spent on food on the table,” she says, smiling weakly.