Kin of ‘Tokhang’ victims need healing

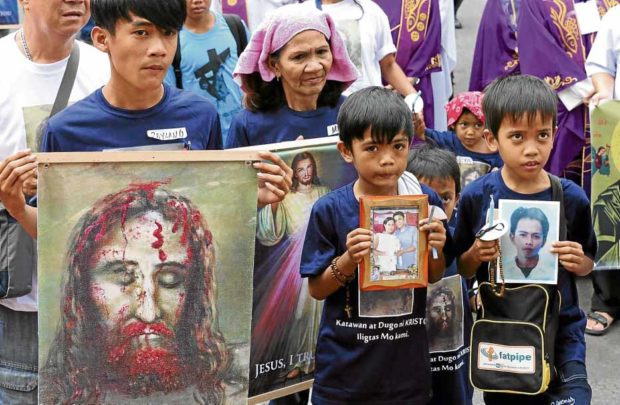

‘ORA PRO NOBIS’ Families of drug suspects killed in the war on drugs join aMass and procession for their loved ones and themselves in Parañaque City. —INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

Ana, 43, and her two teenage daughters are in a huddle on a pavement, putting together shards of colored tiles to form an image of a big tree.

It has been like this since summer: Eight hours daily, Ana works in mosaic art so she can feed and send her children to school.

Healing

But more than that, she needs to calm her tormented soul and heal her grief.

“I find comfort in the idea that no matter how broken a piece of tile is, you can still make something beautiful out of it. So even if our family is no longer complete, I hope something good can still happen,” Ana said.

Ana lost her husband and 19-year-old son to President Duterte’s brutal war on drugs in September last year. She and her four children have been living in trauma and constant anxiety since.

They moved out of their small shanty in a slum colony in Metro Manila for fear that police would kill another member of the family.

Ana’s eldest daughter, a psychology student, dropped out of school to look for a job.

Before tragedy struck, Ana juggled odd jobs, doing laundry and cleaning houses in her old neighborhood.

Her husband augmented her small earnings by working as a drug runner, bringing home P200 to P300.

Now in her new job doing mosaic art, Ana brings all her children—two daughters, aged 18 and 17 and two boys, 11 and 8—to work to make sure that they are all safe.

“We are still shaken by what happened. Whenever my smaller children see a policeman, they tremble and tell me we should all hide,” she said.

Living in fear

Like Ana, 25-year-old Maria lost two members of her family—her father and eldest brother, who was a single parent—in the first wave of the drug killings in July last year.

Although hard up, she took in her brother’s 8-year-old daughter. “Now, I have three daughters in all and I also have to send her to school,” she said.

But because her husband had been identified as a drug peddler, they moved out of their home, entrusting their children to their parents. Now, they see them only on weekends.

Fear has also shrunk their world. “We make sure that we’re home before it gets dark. We also put multiple locks on our door,” Maria said.

Ana and Maria represent the other face of the war on drugs: broken families living under constant fear and trauma, mothers and wives becoming sole breadwinners, and orphaned children.

According to Dr. Ma. Lourdes Carandang, a clinical psychologist and family therapist, the family is the unit of society most hurt by the war on drugs and many such families are either ignored, pitied or blamed rather than helped.

As the government has no intention of easing the campaign against narcotics, she said, it must establish a program that will help the families of those killed recover from trauma and fear, and help them become productive.

Private groups can also take part in this effort, she said.

Priority for children

Traumatized children should be given priority, she said. If neglected, these children could suffer psychological disorders, such as depression, and may even take drugs, she warned.

Dr. Tomas Bautista, a psychiatrist at the University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital, said the benefits of the antidrug war to the community—safer streets and fewer criminals—would be just temporary if the government would not deal with the roots of drug abuse.

“Today, we might feel safer because there are fewer criminals on the loose. But even if we extinguish all adult drug users while poverty persists, the next generation will have the same problem,” Bautista said.

From a clinical perspective, Bautista said, drug addiction is an illness caused by an interplay of genetic and environmental factors.

Poor communities

Poverty, he said, generates citizens who have an unhealthy brain circuit for happiness because they don’t have the right nutrition to produce the building blocks for happy chemicals and also lacked education to balance this.

And poverty, he said, is the reason drug use is higher in poor communities.

Many poor people, in desperate need for gratification and happiness, turn to illegal drugs to turn on the switch responsible for releasing happy hormones in the brain, he said.

“People will just shift to another [addictive substance], like alcohol, or to behavioral addiction, like gambling, as long as poverty fuels [their] desperation for gratification and happiness,” he added.

The overly gratified also falls into drug abuse to satiate too many happiness receptors in the brain, he said.

“I really hope that the government and society [will] further broaden their view of the drug problem,” Bautista said.