Panatag Journal: Sea, Shoal, and a supermoon

An Inquirer team and a four-member crew of an American TV show sailed to the disputed Panatag Shoal (international name: Scarborough Shoal) on Nov. 13, barely three weeks after Filipino fishermen were allowed access to their traditional fishing ground by the Chinese Coast Guard patrolling the area.

The fishermen were anxious about returning to Panatag despite a “friendly agreement” between the Philippine and Chinese governments on fishing at the shoal. But they agreed to take us there so we could see for ourselves the situation at Panatag Shoal.

Our journal of our six-hour stay at Panatag:

8:30 a.m.

Sunday, Nov. 13

Three men with sun-kissed glow were busy loading ice blocks onto a 7-meter wood hulled fishing boat docked in Barangay Calapandayan in Subic, Zambales province.

Another was intently fixing the boat’s alternator, momentarily taking a pause to give orders to three more men who were tying ropes around the outriggers.

They were the fishermen who would take me and Rem Zamora, Inquirer chief photographer, to Panatag Shoal. We were joined by Ryan Leagogo of Inquirer.net and a team of four journalists from China Uncensored, a weekly satire television show in the United States.

The fishermen were scurrying back and forth to prepare the boat for a long (about 24 hours) and nonstop trip to the shoal, 279 kilometers from Zambales.

We were hoping to leave by 9 a.m. but the boat’s alternator was not properly working, forcing Mattias “Mang Bhuboy” Pumicpic, 55, the boat’s owner and skipper, to ask us to wait awhile until the alternator was fixed.

9 a.m. to 11 a.m.

As I watched the fishermen doing last-minute preparations on the boat, the foreign TV crew members stayed under a shade, enjoying their time mingling with the fishermen’s children who appeared amused with their visitors.

Allen Xie, the group’s camera man, and Shelley Zhang, writer/editor, took some snapshots of the kids who seemed to be enjoying themselves.

I even overheard the children, aged 5 to 12, giving the American journalists some Tagalog lessons.

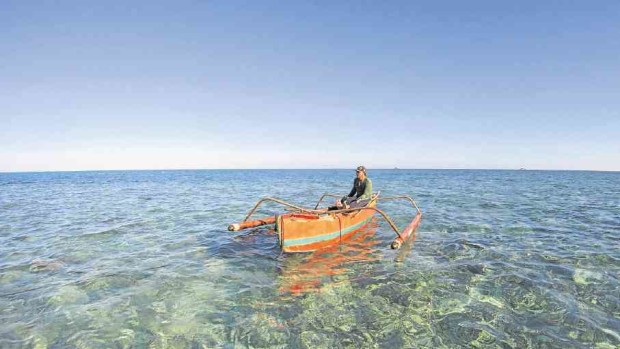

Fisherman Mar Pelayo is happy to return to their traditional fishing ground at Panatag Shoal. Photo by Rem Zamora/INQUIRER

11 a.m. to noon

The boat’s skipper gave us the go-signal to load our bags. His crew of six helped us by putting our stuff into two smaller boats they called “service boats.” Then they rowed the boats until they reached the mother boat, which was anchored 20 meters from the shoreline.

The boat captain told us to wait a little bit more while he took the vessel for a “test ride,” making sure the alternator was working.

When the mother boat returned, each of us boarded it. We took turns hopping from the smaller service boats that fetched us from the shoreline. We carefully tackled the outriggers and brim, balancing our body weights.

A team from the American television show China Uncensored ventures into disputed waters. Photo by Rem Zamora/INQUIRER

1 p.m. to 3 p.m.

The chugging of the engine signaled the start of our grueling and yet exciting journey to Panatag Shoal. None of us seemed to mind the smell of gasoline coming from the bilge and lingering and seeping in the boat.

As the boat started to move away from the shoreline, we felt the strong wind against our face. In no time, the gasoline odor dissipated and we could only feel the fresh and crisp air. Even under a scorching sun, we could feel the tingle of a cold breeze.

Sitting atop Styrofoam boxes at the center of the boat, we shared our expectations and feelings about the trip.

Matt Gnaizd, producer of China Uncensored, asked me if I was excited about it. “I have mixed feelings. I’m both excited and anxious,” I responded. But in reality, I was more anxious.

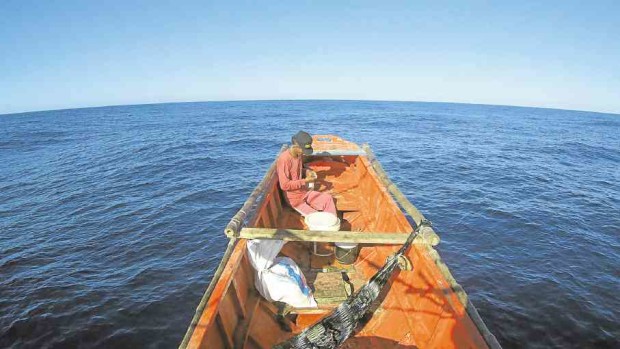

Fishermen use the stern as a dining area, bedroom and, sometimes, a bar. Photo by Rem Zamora/INQUIRER

Gnaizd said he was looking forward to reaching the shoal and was also excited about it. “We’ve planned this trip about three months back. Thank you for arranging this,” he said. He then turned to his three companions to discuss what to do once we made it to our destination.

At the stern (back part of the boat), our cook prepared boiled pork soup for a late lunch. He handed Mang Bhuboy a plate of his dish and offered the same to everyone else. The crewmen feasted on the food at the back.

Except for asking the crew what we would be expecting to see at the shoal, we were quiet in the next few hours.

3 p.m. to 6 p.m.

We fought back our sleepiness to enjoy the view of the vast horizon. As the boat moved even farther, the mountains of Zambales and the rocky islands along the way became small dots before finally disappearing from our sight.

When we were about 20 miles away from our jump-off point, the waves started getting stronger and bigger.

We scampered to secure our stuff to avoid these from getting wet or blown away. We placed our cameras, clothes, food and sleeping bags inside the Styrofoam boxes.

The boat’s crew hopped on the outriggers to tighten the ropes around the four service boats while the skipper continued to navigate the sea that was beginning to get rough.

When everyone got accustomed to the bumpy trip, some of the crewmen took a nap on the outriggers. Others lay down atop the captain’s station.

I felt I needed to find a more stable nook so I went to the back of the captain’s station. There I saw Francisco Fiehl, 55, one of the crewmen. He was standing beside the skipper, holding a piece of paper and adjusting the yellow GPS device.

“What are those numbers on that sheet?” I asked. He said he was trying to set the GPS coordinates of our boat so they could locate a payao (artificial reef).

While he was doing that, a voice on the captain’s radio was telling them where a payao could possibly be found. It was another boat skipper who found the payao on his way to Panatag Shoal a few days earlier.

When Pumicpic spotted a buoy, he yelled out to his crew. “There it is! Prepare your boats. Let’s get something to eat for dinner,” he told them.

In that instance, the crewmen loosened the ropes around the service boats. One hopped into a boat on the right outrigger before it was released into the water. Another boarded a boat on the left outrigger that was sent out to the water as well.

The two fishermen on board the service boats roved around the payao, throwing into the water nylon with several pink paper lures and hooks attached to it.

After 15 minutes of circling the payao, the two fishermen returned to the mother boat with a handful catch, just enough to feed the entire crew for dinner time.

6 p.m. to 9 p.m.

Our cook quickly grabbed the freshly caught fish from the head, slamming each against anything hard before gutting these. He then gently tossed the fish into the preheated cooking oil in a frying pan. In a few minutes, their dinner—crispy, golden-brown fish—was ready.

The crewmen shared jokes as they enjoyed their plate or bowl of rice with a slice of fried fish. They drank tap water placed in a large recycled plastic container.

The foreigners remained on the other side of the boat, having their own dinner—canned goods, bread and bottled water.

After dinner, the passengers prepared to get a restful night. But the crewmen decided to drink a bottle of gin for a few hours before hitting the haystack.

Most of the crewmen slept among the stock of plastic containers at the back of the boat. The cook and another one slept at the crammed makeshift kitchen near the engine.

Rem and Ryan hung their hammocks somewhere in the bow.

Only the skipper would stay awake the entire night. He would call out the names of some of his crew if he needed to leave the steering wheel.

Except for a fluorescent bulb on the boat, it was just the bright moon that would serve as our light during our journey that night. We were still some 161 km (100 miles) from the shoal, the skipper told us.

6 a.m.

Monday, Nov. 14

We could hear the sound of the waves breaking on the boat’s wooden hull and outriggers. The forceful wind would send a shivery breeze.

Last night, I felt a sudden jerk and was awakened by the anxious voice just in front of me. “Are you OK?” Mang Bhuboy asked as he stood and peeped through a window at the back of his station.

It quickly occurred to me that I fell off the bench while sleeping. I went back to the bench and responded, “I’m OK, sir!”

“There were huge waves because a ship passed by. It rocked our boat,” the captain said.

I could not remember if I was able to respond once more. I drifted off to sleep again as if nothing happened despite feeling embarrassed.

It was past 5 a.m. when I was awakened by the chatting crewmen. I was not sure how long they had been up. But they were already busy preparing to fish as the captain cut the roaring engine when we passed by another payao.

“We’re just going to catch fish for our meal later,” Mang Bhuboy said when he noticed I was already awake. The fishermen deployed the service boats around the payao, hoping for some good catch.

Unfortunately, there was not much fish in that payao so the captain decided to resume the trip so we could reach the shoal at daytime.

6 a.m. to 2 p.m.

The crewmen sipped coffee and smoked cigarettes as our boat sailed to the shoal. The captain said we might arrive there past noon, 3 p.m. at most.

When were about 24 km (15 miles) away from the shoal, the boat captain stood, pointed at a distance, and yelled out, “There’s the [Chinese] Coast Guard ship!”

We all looked outside but could not see the ship. “There it is! It’s a white ship,” the captain assured us.

The ship was indeed there, guarding that section of the sea. We knew we would be at the shoal in a few hours.

2 p.m. to 7 p.m.

I eagerly asked one of the crewmen where the shoal was in such a

vast ocean. “You’ll know it’s the Kalburo if the waves are constantly breaking,” he answered.

“We’re already here. This is Kalburo!” Pumicpic hollered, directing our attention to a vast horizon with calm water below it.

Kalburo is the local term for Scarborough Shoal, which at times is also called Panatag (tranquil) Shoal and Bajo de Masinloc.

Two Chinese Coast Guard vessels were stationed at the shoal’s gateway while four other Chinese ships lurked at a distance, about half a mile away where our boat was anchored.

There was a clump of rocks, actually dead coral reefs, appearing above the clear and calm water when we arrived in an almost cloudless afternoon.

When our boat came to a halt, some of the boat’s crew hopped into smaller service boats placed on the outriggers. They loosened the ropes, boarded the boats, and ventured out into the water around the shoal.

Pumicpic told his passengers that the boat would not go beyond the shoal’s mouth or gateway. “It’s risky going near the shoal’s mouth. The Chinese Coast Guard might drive us away,” he said.

There was fear in the tone of his voice that he was trying to conceal. It was if he was avoiding a lion’s den.

“I hope none of those ships will move and approach us. If that happens, we’re backing off,” Pumicpic said.

His uneasiness was an upshot of his personal experience after making several fishing trips to the shoal in the last four years. He was among the Filipino fishermen who were reportedly harassed by the Chinese Coast Guard patrolling the shoal.

But even before the Chinese vessels could be bothered by our presence, the foreigners with us boarded two of the service boats.

They wanted to plant on one of the tiny rocks around the shoal a flag that carried the name of their TV program. They successfully carried it out with ease.

When they went back to the mother boat, it was the turn of the Inquirer team to go to the rocky outcrop. It was only a five-minute boat ride from where we anchored. Two boats took us to that spot.

It was low tide so we were able to see at least 10 rocks poking above the water. The water was just waist-high so Rem, Ryan and I decided to go out of our service boats and plunge into the warm water.

We took turns climbing one of the rocks, taking pictures and interviewing the two fishermen who rowed the small boats we rode. Behind us were the two Chinese Coast Guard ships at the shoal’s mouth, some 10 km away.

After 20 minutes, we returned to the mother boat. We only stayed at the shoal for about six hours because the foreign passengers had to return to Manila the following day.

The fishermen were looking forward to making some good catch even just for a night but had to call it off to take their passengers back to Zambales.

As we sailed back to Subic after sunset, we were greeted by what they called a spectacular celestial show—the biggest and brightest moon in 68 years.

The rare phenomenon made our trip extra special since we were able to view the supermoon from this shoal, which is considered by Filipino fishermen as their paradise. The moon won’t come this close again until Nov. 25, 2034. And we won’t be back to this shoal until who knows.

We left Subic on a fine sunny Sunday hoping to test the waters off Panatag Shoal. Our boat was not intercepted by the patrolling Chinese vessels as we had expected.

It corroborated fishermen’s accounts that they have once more returned to their traditional fishing ground without interference from the Chinese Coast Guard.

The fishermen had barely some catch to bring to their families due to the limited time they had to spend at the shoal.

Pumicpic asked his crew to join him for another fishing trip back to Panatag in the next two days. His son, Junmar, would not join them anymore.

Junmar had abandoned the idea of returning to the shoal after the harrowing experience with the Chinese Coast Guard in the past. Junmar has found a better opportunity abroad. He left the country on the day his father arrived from Kalburo.

It is said that the best day to set sail is Sunday. But nothing is certain and fishermen know it too well.

RELATED VIDEOS