Ibaloy’s fight to reclaim Marcos Park recalled

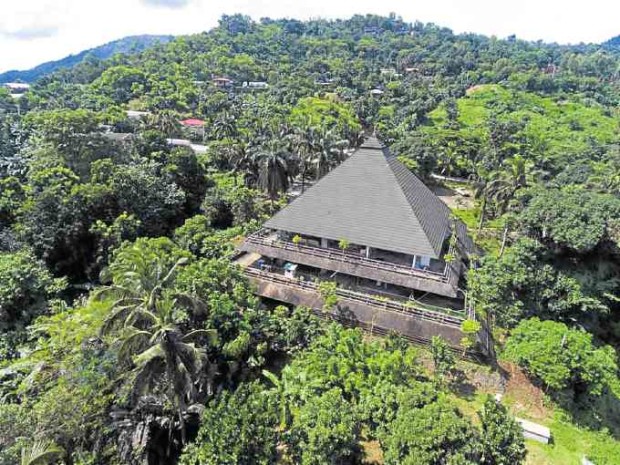

THE CLUBHOUSE in the former Marcos Park stands out amid its verdant surroundings in the village of Taloy Sur in Tuba town, Benguet province. The park was developed into a recreation area, featuring a golf course and a tennis court, during martial law. PHOTO BY RICHARD BALONGLONG/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

TUBA, Benguet—A 27.4-meter (90 feet) concrete bust of the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos once loomed large whenever travelers drove or commuted to Baguio City through Marcos Highway in Benguet province. It was the centerpiece of a proposed Marcos Park that would span 355 hectares of expropriated Ibaloy land in the village of Taloy Sur in Tuba town.

Consisting of a country club, a golf course and a sports complex, the park was being developed by then Tourism Minister Jose Aspiras. But the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolt ousted Marcos and the Ibaloy clans fought to reclaim their land.

No one knew what to do with the bust. When Marcos died in Hawaii in 1989, civic leaders in Baguio debated the idea of keeping it as a reminder of martial law atrocities and abuses. The debate continued for years until communist rebels took that decision away from them. In 2002, half of the bust was blown off.

Ibaloy residents soon exerted efforts to dismantle the bust, said Rose Labotan, heir of an Ibaloy family that reclaimed the park lands. They failed, she said.

“The concrete was so sturdy that even a backhoe could not make a dent. The bust was really made to last,” she said.

People came to scavenge for scrap. The steel frames of the bust meant good money for people “who wanted to share the wealth,” Labotan said, but it took them a whole day to remove a steel bar measuring a foot.

The bust also became a magnet for treasure hunters. Labotan said diggings near the bust started in 2014, which alarmed Ibaloy in the area because of the instability these excavations could trigger.

The remnants of the bust still stand on a 3,000-square-meter lot, which its Ibaloy owners sold to a developer in Tarlac province in 2013. Again, these became a symbol of martial law excess when Baguio activists staged protests there against the planned burial of Marcos at Libingan ng mga Bayani.

“That’s why we are again telling our stories so young Filipinos would know what martial law was all about,” Labotan said.

She lives in what was originally the Marcos Park clubhouse. Her family used to own parts of the grassland which displaced old Ibaloy farms and vegetable gardens.

Labotan took back the land, and grew new trees and vegetables there, before buying the clubhouse from the former Philippine Tourism Authority (PTA) for P250,000.

Ibaloy families were deceived into selling their land to the PTA, she said. In June 1976, PTA officials held a community meeting to discuss plans for Marcos Park, she said. They had acquired the tax declarations of the residents and prepared deeds of sale.

“The illiterate landowners then said they were forced to sign and were given checks, which they referred to as small pieces of cartolina. They did not even know how much they were paid before they were driven out,” Labotan said.

Younger Ibaloy organized themselves to protest their ejection.

Labotan said, “If we allowed the park to thrive, where would we be living now? What would we leave our children and the next generation? It did not feel good to see your parents evicted, soldiers swarming all over your land and your community fenced in. I had to do something.”

Their struggle to reclaim their land gained wider support from the Catholic Church’s social action center led by the late Fr. Patricio Guyguyon and from Cordillera leaders like the late William Claver.

Once Marcos was ousted, the Ibaloy returned to their property.

But the PTA did not give up its claim. In 2001, the agency sued the Ibaloy, claiming rights over Marcos Park, said lawyer Honorato Aquino, a former Baguio lawmaker who represented the Ibaloy in a case in the Regional Trial Court in La Trinidad town.

The Ibaloy won the case, which was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2007. “We were able to prove that the Ibaloy landowners were forced to sign the deeds of sale,” Aquino said.

The golf course has since been converted into rice fields and vegetable gardens.

The Ibaloy family that reclaimed the administration building, hostel, conference hall, view deck and swimming pool donated 2 ha of land to Taloy Sur National High School. The family near the Marcos bust donated a hectare to Salpang Elementary School.

Labotan said the clubhouse, tennis court and the Marcos bust were meant to be donated to Benguet State University, but the institution rejected the offer.

So the clubhouse became Labotan’s home. “The chandelier that was worth P240,000 and the carpets were taken by the PTA. Even the electrical bulbs and wires were removed,” she said.

“But it was fine with me. Anyway, it’s my home again,” she added.