The ‘bagani’ of past and present

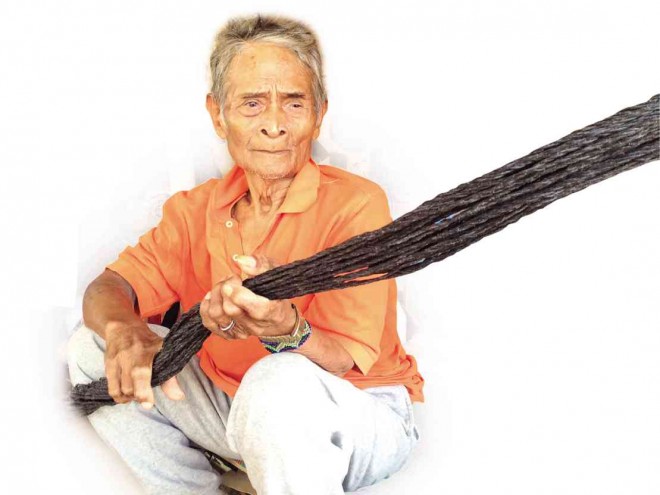

MANOBO chieftain Datu Taday Campos laments the division among the “lumad” created by local officials and groups with interest in their communities’ resources. NICO ALCONABA

In 1994, Datu Guibang Apoga of Talaingod, Davao del Norte province, revived his community’s “bagani” (tribal warriors) and declared war against Alcantara and Sons (Alsons) for allegedly encroaching on the Ata-Manobo’s ancestral land while implementing its Integrated Forest Management Agreement with the government.

Using bows and arrows, Datu Guibang and his warriors attacked Alsons’ workers and the soldiers who were serving as security personnel. After the military filed murder charges against him and several others, the leader had gone into hiding. He, however, was known among tribal leaders as the datu who fought for his people’s land.

Today, the sprouting of armed men in “lumad” communities in Mindanao has exacerbated the plight of residents, who are caught in the middle of decades-long fighting between communist rebels and the government. What has complicated the situation was the fact that local officials had exploited the cultural concept of tribal defenders, arming lumad to fight against lumad suspected of being sympathizers of the communist New People’s Army (NPA).

Last month, Manobo men belonging to the paramilitary group Magahat-Bagani attacked a Manobo community in Lianga, Surigao del Sur province, killing three civilians, two of them tribal leaders, and burning a community cooperative building.

Human rights groups have claimed the militias were being used by local officials and influential tribal leaders as their own security outfits to protect their mining or logging ventures.

‘Lumad’ exodus

Datu Taday Campos, a 91-year-old Manobo chieftain from Sitio Han-ayan in Diatagon village, Lianga, said outsiders with interest in their resource-rich communities were exploiting the bagani concept to divide the lumad. “The lumad are fighting each other. A Manobo kills his fellow Manobo,” he told the Inquirer in a recent interview.

Over 3,000 Manobo men, women and children have fled their upland communities in five towns in Surigao del Sur after the Sept. 1 killings and have sought shelter in the provincial capital of Tandag City. They have endured deplorable conditions inside a virtual tent city at the provincial sports complex.

Life is difficult in the evacuation center, Datu Taday said, but his people cannot return to their villages for fear of being attacked again. “The armed group (Magahat-Bagani) is still roaming around our communities and threatening us not to return. They are our brothers, but they seemed too have forgotten that fact,” he said.

Local officials and militant groups have long accused the military of arming tribal militias in a proxy war against the NPA despite the atrocities they commit against civilians.

Reacting to the Sept. 1 killings, Gov. Johnny Pimentel urged the military to disarm and disband the militias to put an end to the problem of peace and order, which they have been causing for years. “The Army provided the bagani with weapons and bullets,” he said.

NPA using tribes

The military has denied the charge vehemently and has accused the NPA of exploiting the lumad by recruiting villagers from indigenous communities.

“The NPA deliberately destroyed the lumad tribe, its structure, culture and tradition when it deceitfully created Rebolusyonaryong Kalihukang Lumad (Revolutionary Indigenous People’s Movement) and lured tribesmen to join its Pulang Bagani (Red Warriors) Command,” said Capt. Joe Patrick Martinez, spokesperson for the Army’s 4th Infantry Division.

Communist rebels, Martinez said, “sparked the conflict within the tribe by pitting its Pulang Bagani against traditional bagani,” referring to the anti-NPA militias.

A number of tribal militias operate in the provinces of Agusan del Sur and Surigao del Sur. Among these are Magahat-Bagani and a suspected private army of Datu Calpit Egua, a Manobo chieftain in Agusan del Sur who is into small-scale gold mining.

Last year, communist guerrillas attacked Egua’s compound in Prosperidad, Agusan del Sur, sparking an hours-long gun battle that left 17 people, mostly guerrillas, dead.

Datu Taday, the Manobo chieftain from Lianga, said the military had been somewhat involved in abuses committed by militias in his community.

“This started when soldiers went to our community and told us we could not prevent outsiders from entering our village to do logging or gold mining. We have no quarrel with the group of Caltik (Calpit),” he said.

No longer existing

But there is no reason for the bagani to exist, Datu Taday said, because the present situation no longer called for it. “We used to take revenge to settle disputes. If one of our own is killed, we retaliate. But now, we have the government. We cannot take matters into our own hands,” he said.

The bagani, as part of the tribe, had long ceased to exist, the leader said. “I don’t know exactly when, it was a very long time ago, it could be traced back during the Spanish era, when the different tribes entered into a tampuda (agreement) that ended the tribal wars.”

For Datu Taday, a tribal war occurs when a tribe fights another tribe. “What’s happening now is not a tribal war because these Magahat-Bagani are Manobo. The people they are killing are also members of the Manobo tribe,” he said.

He advised those under his clan not to take part in the violence, either as pro-military militiamen or as NPA rebels. “Our only enemy are the weeds because we are farmers. We want to live in peace,” he said.

At least nine lumad and an advocate of lumad rights were killed by security forces and their allied militias in Mindanao between August and September this year, according to the human rights group, Karapatan.

On the other hand, the military has accused communist rebels of killing lumad. Martinez, the Army spokesperson, said 357 lumad had been killed by the NPA from 1998 to 2008 in Mindanao, while anticommunist tribal militias in Caraga region had killed 18 Pulang Bagani warriors and 13 non-lumad rebels from 2010 to 2015.

Loreto killing

The military also accused the NPA of abducting and killing Mayor Dario Otaza of Loreto, Agusan del Sur, and his 27-year-old son in Butuan City on Monday.

A Manobo, the elder Otaza was an NPA rebel who surrendered to the government in 1986 after strongman Ferdinand Marcos was ousted from power. In 2013, he became mayor of the landlocked Loreto town and helped in “liberating” his town from the communists.

He was said to be responsible for the surrender of 246 lumad NPA fighters.

But the NPA accused Otaza of organizing and arming a militia blamed for sowing terror in lumad communities in Loreto, leading to massive displacements of civilians in 2013.

“The attack on Mayor Otaza was a clear and undeniable proof of the NPA’s human rights atrocities in lumad communities,” said Maj. Gen. Oscar Lactao, the 4th ID chief. “This is also a solid proof of the NPA’s continuing campaign to take control of our lumad and anyone who gets in their way is killed in the process.”

Almost two months after the killings in Lianga, the members of Magahat-Bagani remain at large despite the police and military’s promise to go after them.