In Baguio museum, flags celebrate victories

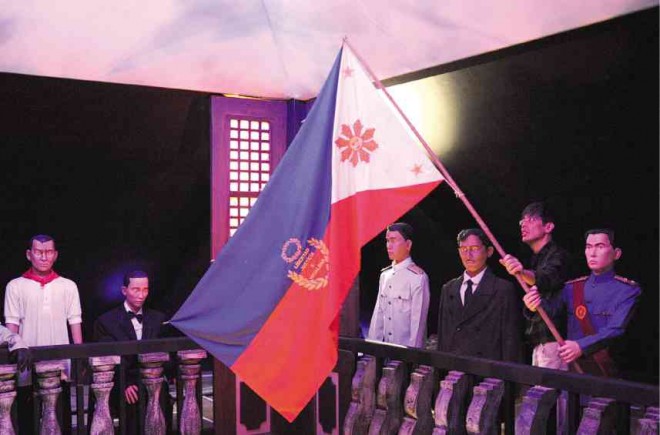

FIRST FLAG This artist rendition of the creation of the first Philippine Flag is featured in a Baguio museum that stores the actual relic. Emilio Aguinaldo Suntay III, great grandson of the late former president Emilio Aguinaldo, says fabrics and materials were purchased from Hong Kong. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

BAGUIO CITY—-Aside from the original Philippine flag that was raised on June 12, 1898 in Kawit, Cavite, the other flags of revolutionaries are on display in a quaint interactive museum here that was put up in honor of the late Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo.

But museum visitors must take in the victorious battlefield stories of these flags, and not the defeats for which the banners have been associated with in many history lessons, said Emilio Aguinaldo Suntay III, Aguinaldo’s great grandson.

Suntay is the executive director and administrator of the family’s Emilio Aguinaldo Museum here, which has been home to the original Philippine flag.

Prized artifact

The flag is the museum’s most prized artifact, which is unique because it bears a face stitched into the banner’s image of the sun. It also has a lighter shade of blue on the side that signifies peace time.

Article continues after this advertisementTattered and fragmenting, the flag is sealed tight in a glass case at a temperature-controlled alcove, with only dim shafts of sunlight providing illumination.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Aguinaldo museum has tried to engage the interests of young Filipinos so they can see the first flag before its silk fabrics become worn beyond repair.

But equally important to Filipinos is the red, white and black battlefield banner, also on display at the museum.

Bloodstained but in better condition compared to the museum’s prized relic, this banner was carried on the shoulders of three men through many of Aguinaldo’s battle zones.

It has three stars, each bearing a face, that may have been inspired by the original flag’s human-like sun, said Suntay.

Captured

But Aguinaldo’s battlefield flag was confiscated when the general was tricked and captured by a small band of American soldiers and their Macabebe mercenaries in Palanan, Isabela, in 1901.

Further inside the museum is a case containing the battle flag used by young Gen. Gregorio del Pilar. The flag was recovered from a Spanish regiment Del Pilar defeated shortly before the Philippine-American war broke out.

The Del Pilar flag, however, had been associated with Tirad Pass, the narrow passage way in the Ilocos region where the young general and 51 of his 60 soldiers died as they fought about 500 American soldiers in 1899.

Filipinos had fought a guerrilla campaign against the well-armed Americans, and the battle in Tirad Pass gave Aguinaldo time to evade his pursuers as he made his way through Northern Luzon.

These flags were collected and preserved by Suntay’s grandmother and Aguinaldo’s youngest child, Cristina Aguinaldo, when she relocated to Baguio City.

According to Suntay, his grandmother found the original flag tucked in Aguinaldo’s death bed. She brought the flag to Baguio, whose cool climate was presumably a better environment for old flags, he said.

They also kept the existence of the flags a secret.

THE BATTLE flag of Emilio Aguinaldo, which features faces drawn on three stars, was carried by three men in each of Aguinaldo’s battles to liberate the country, during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War. It is kept on display at a museum administered by Aguinaldo’s great grandson, Emilio Aguinaldo Suntay III. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

Protecting the flag

Suntay said Aguinaldo protected the flag by informing American colonial authorities he lost it during the war.

The American point of view focuses on the defeats, not the victories of the Philippine-American war, Suntay said.

“We displayed the battlefield flags so we can finally tell the story of that war from our point of view,” he said. “For instance, Del Pilar was an accomplished general, based on the Spanish colonial government’s own account. He fought them and won a month before the declaration of Philippine independence in 1898, but we hear little about that story when we celebrate Independence Day.”

American historians called it an insurrection, Suntay said, to muffle the impact of the war on the US.

But even these historians acknowledged that the “Philippine rebellion” had been costly and divisive for the American public during that era.

Most divisive

An account of Aguinaldo’s capture in Palanan on March 23, 1901 described the Philippine-American war as “the most divisive conflict” for America, next to the American Civil War and the Vietnam War.

It also described the capture as “one of the most daring exploits in US Army history.”

To suppress the rebellion, the US government deployed a small band of American soldiers who pretended to be prisoners of war to get close to Aguinaldo in Palanan.

Aguinaldo’s battle flag was also taken but it was returned to him by US Ambassador Charles Bohlen on June 12, 1957, according to museum records.

“We don’t celebrate battle flags at all, but these flags and their stories have become relevant nowadays especially with the archipelago’s sovereignty and territorial integrity under threat from countries like China,” Suntay said. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON