Day and night

Without Caravaggio one might not fully understand Bernard Strozzi’s painting of Zacchaeus. We know Zacchaeus’ story. He was a chief tax collector. In his Gospel, Luke narrates that, when Jesus was passing through Jericho, Zacchaeus wanted to get a look at him. But because of his height, he could not see Jesus over the crowd, and so Zacchaeus did the next best thing, climb a tree. When he came to the place, Jesus saw him and said, “Zacchaeus, come down quickly, because I must stay at your house today.”

Without Caravaggio one might not fully understand Bernard Strozzi’s painting of Zacchaeus. We know Zacchaeus’ story. He was a chief tax collector. In his Gospel, Luke narrates that, when Jesus was passing through Jericho, Zacchaeus wanted to get a look at him. But because of his height, he could not see Jesus over the crowd, and so Zacchaeus did the next best thing, climb a tree. When he came to the place, Jesus saw him and said, “Zacchaeus, come down quickly, because I must stay at your house today.”

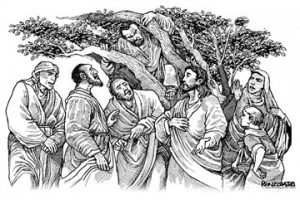

One would think that in painting this scene Strozzi would put the spotlight on Zacchaeus. But Strozzi did not do this. He focused the light on Jesus talking to five or six men. The rest of the picture – including Zacchaeus who sits on the two forking branches of a sycamore tree – is in darkness.

Strozzi, who lived towards the end of the sixteenth century, was just ten years younger than Michaelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), whom he outlived by 34 years. In effect, they were contemporaries. No doubt Caravaggio was the dominant painter. He strove for realism and often – even in the case of biblical themes – he used true-to-life characters, and portrayed them, warts and all, directly on canvas, without preliminary sketches, without the usual preparations. To give his paintings a dramatic quality, he made use of darkness, shadows, which starkly contrasted with the light. This earned for him and his followers the name “tenebrists” or “shadowists.” As someone aptly remarked, Caravaggio put oscuro into chiaroscuro.

Such was Caravaggio’s power that Strozzi could not completely release himself from his apron strings. But Strozzi refined Caravaggio’s raw realism with a little gentleness. And so except for this in Strozzi we see about the same employment of darkness, which turns the scene into that of night, and reveals only whatever of the landscape the light claims.

Might not Strozzi’s reticence to yield to the shadows come from his being essentially a good man? At age 17 he joined a Capuchin monastery, but after ten years, when his father died, he left to support his mother with income from his paintings.

On the other hand, Caravaggio was the kind who, after working briefly, would party hard for months on end, and always got himself into brawls, and on one such occasion he killed a young man. There was no contemporary of his but failed to notice his tendency to use as models persons of ill repute.

As one looks more closely at Strozzi’s painting of Zacchaeus, one’s attention is drawn to someone in the foreground, who stands beside Jesus, at his left. The illumination falls on him equally as, if not more than, it does on the others. At first glance, because of his smallness, he seems like a child, but his calves and biceps and lean face betray his adult years. Why, he is no other than Zacchaeus himself.

In Strozzi’s painting, Jesus gestures towards the little man, as though saying something in his favor.

What happened after Zacchaeus came down from the tree was that the people complained that Jesus had made himself a guest of a tax collector, a sinner. But Zacchaeus said, “Look, Lord, half of my possessions I now give to the poor, and if I have cheated anyone of anything, I am paying back four times as much!”

And in reply Jesus said, and this was the moment Strozzi sought to put across with his brush, “Today, salvation has come to this household, because he too is a son of Abraham! For the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost.”

In effect, the painting shows us two versions of Zacchaeus – one in the dark sitting on a branch of the sycamore tree, and one in the brightness beside Jesus. The two versions represent Zacchaeus’ past and present.

When Caravaggio did a painting about the conversion of St. Paul, he was taken to task for putting the horse in the middle, rather than the saint, who lies on the ground. Caravaggio explained rather cutely that the horse “stands in God’s light.”

In his painting, Strozzi seems to say that, more than for Jesus to have dinner in the tax collector’s house, Jesus’ invitation was for Zacchaeus to come down and emerge from the darkness quickly and fully share in God’s light.