Origins of Benguet mummification

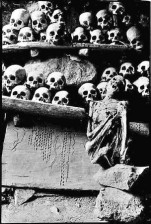

IN REPOSE throughout the centuries, a mummy is interred with rows of human skulls at the Opdas burial cave in Kabayan, Benguet, in this 1981 photograph. Carving detail beside the mummy shows samples of tattoo designs preserved on the skin of some of the mummies. TOMMY HAFALLA/CONTRIBUTOR

The sciences, both human and applied, are picking up from where oral traditions left off in explaining lingering questions over the practice of mummification in Benguet.

But scholars and experts still differ over several key aspects of a practice that has been extinct for centuries. For instance, the jury is still out on the determination of the basic substance that would preserve the cadaver.

Scientists from the National Museum sustain oral accounts that salt was the primary ingredient in preserving the remains of at least 12 mummies interred separately in the Timbac and Tinongchol rock shelters in Kabayan, Benguet.

Orlando Abinion, a chemical engineer and conservation project coordinator of the National Museum, says “salt solution” was fed through the mouth of the recently deceased causing a body to dehydrate.

This process draws parallelism in the mummification by ancient Egyptians where the corpse is placed in a tub of salt for desiccation, he says. “The difference is that while the Egyptians embalmed their dead, nothing was taken out of the Kabayan mummies,” he says.

Research updates presented at the University of the Philippines Baguio on Feb. 13 by Abinion and anthropologist Maritess Paz Tauro speak of the National Museum’s initiatives to expand research on the Kabayan mummies using forensics and the social sciences.

Tauro says a close examination of the mummies has allowed them to determine some specific details on the mummified individuals. “The structure of the cranium has provided insights as to whether the mummy is typical male or female,” she says.

The scientific survey is part of the inventory and cataloguing processes being done to establish a reliable body of knowledge on the mummies of Kabayan.

Systematic vandalism

However, Tauro says even science is stymied by the systematic vandalism done on the mummies in the last century since the most prominent of these, “Apo Anno,” was stolen in 1906.

“Dental structure would have given us an estimate of the age of the cadaver at the time of death but this is already unreliable because in some, the absence of dentition (teething) indicates this was done post-mortem,” she says.

Tauro says souvenir hunters in the past had the tendency to pilfer parts of the cadaver—often taking a tooth or a finger—such that as far as the mummies are concerned, scientists can no longer study a pristine specimen.

There are parts of the dead, however, that can still speak audibly through the centuries. Tauro says the staining of the teeth suggests the active chewing of betel nut during the natural life of the individual.

Body art

Tattoo details, remarkably preserved especially in the case of Apo Anno, are virtual symbolic records of the life of the individual.

Abinion, who has handled Apo Anno for the past 15 years, says parts of the mummy’s body art show animal figures, which suggest that “he must have been a hunter.”

Detailed explanation of Apo Anno’s tattoos is found in “The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practices,” a 2012 journal article by Dr. Analyn Salvador-Amores, UP Baguio assistant professor of social anthropology.

She writes that Apo Anno might have belonged to a group described in the Ilokano epic, “Biag ni Lam-ang,” as “Igorot a burikan (spotted Igorot).”

Amores says the “burik” patterns were “kin-based and had social and collective meanings among the Ibaloy.” The details on Apo Anno’s tattoos are similar to the 1885 monographs of German scientist Hans Meyer, Amores says. “They appear on the mummy of Apo Anno, which is estimated to be 700 to 900 years old,” she says.

Widespread practice

Unlike tattooing which is an individualized practice, mummification appears widespread when it existed in Benguet, says Tauro. This is seen in the varied ways in which the dead were displayed, indicating that there might have been a good number of people who knew about the process.

This is because it is likely that the people might have stumbled into the practice in the course of their agricultural practices, says Dr. June Prill-Brett, an anthropologist who was part of a team of anthropologists who surveyed the Kabayan mummies in the late 1960s.

“Pre-Hispanic farmers in Benguet discovered that bacterial lesions on their cattle can be cured using the juice extracted from the patani (Lima bean),” she says. “By association, the farmers must have thought: if the juice can stop the flesh from rotting, this could be done to preserve the dead as well.”

This challenges the belief that salt solution was used in the mummification process.

“Salt was a trade commodity in the highlands and is valued in gold in today’s standards,” says Cordillera photographer Tommy Hafalla. But he says “even the wealthiest “baknang” of the Ibaloy could not have used salt in preserving their dead.”