Century-old trees mute witnesses to history

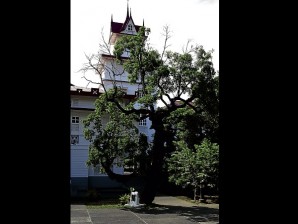

AGUINALDO'S CHICO. The Chico tree (Manilkara sapota L.), one of the trees in the backyard of the Emilio Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite province, was planted by General Aguinaldo himself and was said to be one of his favorites, according to former museum gardener, 70-year-old Vener Vales. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

(The author is History Researcher at the National Historical Commission of the Philippines)

If only trees could talk, they would regale us with historical tales they have witnessed firsthand.

They are the living links to the past that no man has recorded.

Trees are ultimate symbols of strength and fortitude. It’s a pity they could only witness, not join the Philippine Revolution. But be a witness, they did.

The centuries-old Kalayaan Tree or Siar (Peltophorum pterocarpum), located in a churchyard in Malolos, Bulacan province, has been a living witness to many historic events that transpired in the area. It was in Barasoain Church where three important events of our country took place: the convening of the First Philippine Congress on Sept. 15, 1898; the promulgation of the Philippine Constitution, popularly known as the Malolos Constitution on Jan. 21, 1899; and the inauguration of the First Republic on Jan. 23, 1899, establishing the Philippines as the first democratic country in Asia.

The Siar was then a young tree standing a few meters from the convent where Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo found temporary refuge. Revolutionary field officers waited under its shade to see the general and report on the battles won and lost by the revolutionaries. It was where Katipuneros waited for battle orders or military mission.

Townspeople cheered Aguinaldo by this tree as he looked out the window or as he rode in his carriage on his way to the congress session at Barasoain Church.

Set on fire

When Aguinaldo left Malolos, the convent headquarters— with all the important government papers—had to be burned. The Siar tree was badly damaged but it has managed to survive.

Earlier, on the same plaza fronting the historic edifice, daring young women bravely stood before visiting Spanish Governor General Valeriano Weyler and presented a petition for the opening of a night school. Jose Rizal admired the courageous act of these women of Malolos that he wrote a letter in honor of them.

On Saturday, beneath the shade of the tree is a monument depicting the meeting of Filipino revolutionaries represented by Generals Gregorio del Pilar and Isidro Torres, legislator Don Pablo Tecson, nationalist Church leader Padre Mariano Sevilla and freedom fighter Doña Basilia Tantoco.

Siar is a hard and durable tree. It is not a native species although it is not known how it reached the Philippines. It has adapted itself well in different parts of the country and is now widely found in Luzon and Mindanao. It is planted as an ornament because of its bright yellow flowers.

The chico tree (Manilkara sapota L.), located in the backyard of the Emilio Aguinaldo Shrine in Kawit, Cavite province, was planted by the general. Reportedly one of his favorites, the tree was a mute witness to his intimate talks with his comrades of the revolution and of gatherings such as the proclamation of Philippine Independence on June 12, 1898.

Aguinaldo spent restful hours under the shade of this tree. When he retired to his home in Kawit, he reportedly wrote his memoirs under the shade of the chico tree, a tropical species which reached the Philippines from Mexico through the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade.

The Kapitan Idong Tree (Magnifera indica), a mango tree named after Dasmariñas, Cavite, revolutionist Don Placido Campos, had been a witness to the historical event of Feb. 25, 1897, when Spanish troops massed under its shade to attack the Catholic Church, then held by the revolutionists. After six months, the Spanish Army came back and launched an attack on the church to regain the area. The revolutionaries fought hard but failed due to the superior arms of the Spanish forces. After the Filipino-American war, a civil government was established and Kapitan Idong was chosen president of Dasmariñas.

Katipunan Tree

The Katipunan Tree (Eugenia cumini), so named after the revolutionary society founded by Andres Bonifacio on July 7, 1892, was a duhat (Java plum) tree located in Barangay Kaligayahan, Novaliches, Quezon City, birthplace of the revolutionary heroine Melchora Aquino, popularly known as “Tandang Sora.” The tree was named after the revolutionary organization to perpetuate the memory of Katipunan’s role in fighting for our freedom.

Every June 12, a simple Independence Day celebration takes place in the area under the joint auspices of the Knights of Columbus-Novaliches District Assembly of the Saint Maximilian Kolbe Parish Church and Metro Manila College.

The Death March Tree (Tamarindus indica L.), a sampaloc (tamarind) tree located between Kms. 121 and 122 National Highway, Sta. Rosa, Pilar, Bataan province, had also seen many historic events. On April 10, 1942, it witnessed the suffering of the Filipino and American troops who marched by this area after the surrender of Bataan to Japanese forces.

Historical markers

In the 1980s, these trees were recognized by the National Historical Institute and the Tree Preservation Foundation of the Philippines for their historical significance. Markers were placed around them, extolling the historicity of events that transpired in their respective areas.

Trees are one of the most fascinating creations of God. A tree may grow to an incredible size and live to an almost unbelievable age.

There are trees which are considered historical and there are those connected with religious beliefs like the Bodhi tree, a sacred fig tree under which Buddha obtained enlightenment. The Anne Frank tree, a horse-chestnut tree in the city center of Amsterdam, which was mentioned in Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl,” was a sacred tree of remembrance for Holocaust victims. Unfortunately, the tree was destroyed in a storm in 2012.

Not a few old trees found in different areas in the Philippines witnessed various events in our history or were part of momentous events. They were the silent witnesses of our past. However, it’s sad that many trees, especially in Metro Manila, had been cut down due to road widening projects, construction of buildings or subdivisions. Because of progress, old trees are being taken down from the roads— and out of our memory.

Sources:

Agoncillo, Teodoro. History of the Filipino People. Garotech Publishing, Quezon City. 1990.

Lansigan, Nicolas P. Living Links with our Past. Herald Printing Services, Mandaluyong, Metro Manila. 1983.

Medina, Isagani R. Cavite before the Revolution. CSSP Publications, Quezon City. 1994.

Tiongson, Nicanor G. The Women of Malolos. Ateneo de Manila University Press, Quezon City. 2004