Paracale mining: A way of life, death

(In many areas, small-scale mines sprout like mushrooms as soon as word of gold underneath the land spreads. How can poor, jobless people resist the lure of striking it rich with gold prices now at $1,750 per troy ounce and an estimated reserve of 4.9 billion metric tons of gold worth P7.36 trillion as of April this year, scattered throughout the Philippines, according to the National Statistical Coordination Board. The correspondent visited one community in Camarines Norte where the search for the precious metal has become a way of life, and death in some instances. —Ed.)

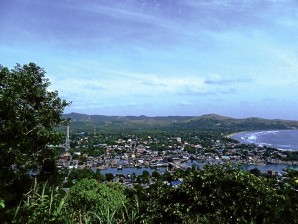

PARACALE, Camarines Norte—For some residents, Paracale is like Endora in Johnny Depp’s movie “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?” It is a place where people are busy, yet nothing much happens.

Despite being gold-rich, Paracale remains a sleepy town. It is dependent on the internal revenue allotment from the national government as a third-class municipality with an annual income of, at most, P45 million.

To earn a living, many people choose among mining, fishing, working in stores and shops, and looking for jobs elsewhere. The luckier few get stable government jobs.

Among these options, mining lures most of the people. This makes them subsist primarily on gold deposits beneath the hills and shores of one of the Tagalog-speaking towns of Camarines Norte, the northernmost province of Bicol.

Jay Constantino, 29, married but yet to have a child, is one of those residents who choose to make a fortune out of gold ores. He does not mind that mining for gold is an unsure, shaky source of income.

In August, he lost his job as a driver in Metro Manila and was convinced by his in-laws to settle and try his luck in Paracale instead.

He says, given a chance, he will still choose mining over having a stable source of income or steady job.

A matter of luck

“In mining, it’s possible to have luck on your side and strike gold and earn more than a regular job can provide,” he says.

According to him, many town residents have been able to build sturdy and beautiful houses after finding large quantities of gold especially in makeshift mines dug along the town’s shore area.

He dreams of getting the same break even if this is not an easy path to riches.

In Paracale, mining is gambling and literally going down what could be a grave.

Not all ores extracted from the deep, narrow, interconnected tunnels yield gold even after piled-up expenses that include the cost of materials such as picks, shovels, mallets, ropes, wood, air compressors, electric bulbs; and the cost of human and other capital needed to dig out the tons of dirt that conceal gold ore, called “beta” by local miners.

In Paracale, both financiers and miners have to know beforehand that all the ventures can boil down to just a pile of dirt.

A maze of ‘drives’

To reach the gold ores, miners also have to dig and crawl into about 50-meter deep mining tunnels that eventually maze out into lateral passageways called “drives,” which can lead to more vertical, deeper excavations depending on the availability or locations of the ores.

The deeper a tunnel is, the less air it has for miners to breathe in and the higher the risk of miners being suffocated or buried alive.

Constantino and dozens of other townsfolk, especially those who are poor, are familiar with the risks. But, for them, the risks are part of daily life.

“It is only scary when it’s your first time. Fear gradually fades away,” says Constantino.

In Paracale, most of the mining tunnels are located not far from the town proper. In Barangay Palanas, most of these tunnels are on the sides of the hills that overlook the town proper.

With nine other companions, including a team leader, Constantino has dug a 20-meter hole leading to a possible ore. It is getting deeper because they have yet to hit an ore or a hint or trace of it.

To prevent the hole from crumbling and burying the miners, pieces of wood are mounted on the sides of the hole.

The hole is pitch-dark and is only illuminated by an electric bulb lowered into it.

To descend, miners cling to a rope slowly lowered into the tunnel until they reach the bottom.

When power runs out and causes the compressors that pump air into the hole to stop running, miners have to climb out within 30 minutes or die of suffocation.

Extra care has to be observed since anything that falls into the pit, even a pebble, can turn into a free-falling projectile that can injure the diggers below.

Deadly water

Another danger is water rushing into the hole and drowning all those inside it.

This exactly happened on Jan. 29 in a seaside mining pit in Palanas. Seawater rushed into the mining pit and drowned two small-scale miners.

The accident prompted Gov. Edgardo Tallado to order all small-scale mining operations in Paracale shut down.

Mining activities did stop, but only briefly. Soon, many were mining again.

Although seaside mining is more dangerous compared to hillside mining, more miners are drawn to it because ores are more plentiful in the coastal areas, miners in the hills say.

What prevents more miners from digging on the seaside is that much of the area had been claimed by other small-scale miners.

Family business

Mining in Paracale is a “family business.”

“It’s better if all those working on a venture belongs to one extended family because there’s trust issue involved in mining,” Constantino says.

“There are times when some miners would find free gold (gold in free or uncombined state) and run away with it. Situations like that are minimized when everyone is a family member,” he adds.

Despite the toil, each miner, on a not-so lucky day, can only earn from nothing to P500 in a week. The income is so irregular that the average take-home money for a month is only about P4,000, say several miners in Palanas, including Constantino.

Archie Maraña, 31, like Constantino, has mining as his source of livelihood. “Since I was a child, I have been into mining,” says Maraña.

What he does is to ask for low-grade ores from miners uphill and spend the whole day pounding it with a mallet before the ores can be put into a ball mill for grinding.

A ball mill is a drum-like machine that grinds rock into a fine powder until it becomes a slimy, viscous mixture. It is hollow and filled with heavy rods inside and pulverizes rocks by being rotated by an engine, which causes the rods inside to move and pound the rocks in the process.

Maraña has stayed on with this job despite very little earning. Most of the time, he gets nothing. The hope that one day he will hit it big keeps him going.

In Paracale, the financiers are the ones who get rich from mining, says small-time financier Alex Dela Cruz, 40. “Miners do not get rich here,” he quips.

Each gram of gold is bought by gold traders in the town proper for P1,600. The financier gets the bulk of the proceeds while as many as 20 miners share the remainder.

“The only chance for a miner to earn big is for him to dig out free gold and run away with it,” says Dela Cruz.

But he knows of a few miners who were lucky to earn big only to end up in the poorhouse again because they simply threw the money away on vices.

He says most of those engaged in mining in Paracale are those who did not finish schooling because of either financial inability or the choice to stop schooling.

Toiling children

Child labor also proliferates in the town, reveals Dela Cruz, because once 12- to 15-year-old children can do the job, they are allowed by their families to take part in mining.

“As long as they can be tapped to help,” says Dela Cruz.

He says the lure of money makes some parents decide to let the children do tasks such as transporting ores into the ball mills downhill.

Gradually, what happens is either the child or the parent loses interest in pursuing education after realizing that it is easier to get money from mining compared to years of schooling.

Dela Cruz talks of the situation in his neighborhood, which is the same experience in mining communities like his town.

In Paracale, a day usually starts with miners trekking to the hills or the seaside, each of them carrying mining equipment.

But on rare (and dreaded) moments, it ends in a mining pit turned into a grave for poor, desperate miners eaten by dreams of a better life.

Photos by Jonas Cabiles Soltes