Zambales bore brunt of Mt. Pinatubo’s fury

(Last of two parts)

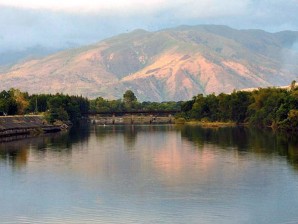

‘ECO CAMP’. From the ashes of Pinatubo’s eruption, the Eco Village rises by the banks of the Cabatuhan River in Iba, Zambales, where resettlers are immersed in organic farming, tree planting, river protection, mangrove plantation and proper solid waste management. Photo courtesy of ABS-CBN Foundation

IBA, Zambales—Residents of this province are still struggling under the weight of lahar that rolled down the slopes of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 and the ashfall that settled and irreversibly changed the landscape.

Zambales bore the biggest damage to public infrastructures in 1991, data from the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) showed. Yet, among the three provinces where the volcano is nestled, Zambales is seen as the least-assisted even though dikes there undergo rounds of damage and repair.

In Botolan town, where Pinatubo’s eruptions left an indelible imprint on the minds of its people and placed a heavy burden on their lives, a resettlement can still be found—one of five still existing in the province.

Remedios Raquiel, 51, an Aeta from the Baquilan resettlement, said memories of what happened would be with her “until my last days.”

“I remember the sky getting darker in the middle of the day and the earth was shaking. People were fleeing and animals were [wailing],” she said.

Her daughter, Gemma Ramos, who was 8 years old in 1991, said: “It was a very hard time. I grew up through the worst of it. There was no food or water, and we depended on others to give us that and provide shelter.”

Gemma is now married at 28 and has two children. What depresses her was another instance of misfortune in 2009 when Typhoon “Kiko” and Tropical Storm “Ondoy” hit the province, and the flood swept away their houses.

“We had to go to the resettlement sites once more. They say that the water and mud fell from the mountains and broke the [Bucao] dike, and I think that is still because of Pinatubo. I’m sad that my children have to live through this [ordeal] again,” she said.

Pinatubo legacy

Gov. Hermogenes Ebdane Jr. said Pinatubo’s legacy in the province would be “felt for a long time.”

“Even though there was greater damage to property and lives in [Pampanga and Tarlac], they were able to reconstruct [and move on] soon after the initial eruption because they are [situated on a plain],” he said.

In Zambales, the remaining sand and lahar deposits on the slopes flow down from Pinatubo and drain to the West Philippine Sea (South China Sea) through major river systems.

“Whenever there is a storm, this sometimes results in flooding in the affected portions of the province, like the towns of Botolan, San Marcelino, San Felipe, San Narciso and San Antonio,” Ebdane said.

Destructive lahar on the heels of typhoons in Botolan, especially in 2002 and 2009, served to remind government of the need to protect the town.

Projects

Zambales received P200 million from the Office of the President in 2009, but the amount went for the repair of the Bucao dike, a new bridge and drainage structures.

Ebdane, a former public works secretary, said rehabilitation projects, such as the Pinatubo Hazard Urgent Mitigation Project, were not implemented in the province due to lack of funds. The project needed P4.9 billion for Zambales alone.

“At present, it’s still in Phase 3, [covering] Pampanga projects [until] the fourth phase. The fifth phase, which is [focused on] Zambales, has not been funded yet,” the governor said.

Hercules Manlicmot, Zambales district engineer, said the river systems were heavily silted.

“About 80 percent of [volcanic materials] fell on the Zambales side, and the other 20 percent in Pampanga and Tarlac. Of that 80 percent, most of it went to the Bucao and Maculcol rivers. When there’s heavy rain, they will overflow if not desilted [and spawn floods that destroy infrastructure or damage crops],” he said.

Keeping rivers deep

Schools, roads and bridges have been restored and rebuilt, he said. “What we have to watch out for now is keeping the rivers deep enough so that sand and lahar can flow to the natural catch basin of the [West Philippine Sea] when it rains.”

Provincial agriculturist Rene Mendoza said agriculture had been crippled by the eruptions. Irrigation systems were destroyed, leading to the decline in farming activities and poultry production.

Olongapo Mayor James Gordon Jr. said his city, the major commercial center of Zambales, had recovered after 20 years. “Life goes on. We didn’t go backward, and we are still going forward,” he said.

He said the city’s recovery was made possible by 8,000 volunteers led by his brother, then Mayor Richard Gordon.

“Our experience here taught us that disaster prevention should be at the forefront, and we must group together when disaster strikes,” he said.

Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority Administrator Armand Arreza, who was one of the volunteers in the early 1990s, said he saw how empty and abandoned the city was after the eruptions. “[But through it all] you could see that the community spirit was very strong.”

Lands, safety

Records from the National Housing Authority show that the government had issued 11,974 titles for the 48,845 homes and lots it had built in 16 lowland resettlements in Central Luzon since 1992.

It was only on the 19th year after the eruptions when the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples began giving out certificates of ancestral domain titles (CADT) to tribes living on Pinatubo’s flanks.

Among these, the CADT application of 508 Aeta families over 13,723 hectares in Crow Valley in Capas, Tarlac, appeared to be more contentious because the site is used by the Philippine and United States military for war games.

In 1998, Jaime Sinsioco and Ramona Julabar of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) had advised local governments and residents in Central Luzon not to let their guard down, especially against floods and lahar flows.

“Though Pinatubo might not be restive again in the near future, it left a trail of hazards which will keep the residents and government agencies preoccupied with planning programs to minimize the risks brought about by these,” they said.

“These problems will continue to persist even decades after the eruption. Thus, long-term planning is a must.”

Gaps in implementation

In a brief assessment, the Neda acknowledged that “while preparing its comprehensive rehabilitation master plans, the government was also preoccupied planning and implementing urgent postdisaster responses consistent with the twin strategies of containing flooding/lahar and restoring/enhancing access.”

Neda said the gaps in plans and implementation were “the result of the government’s financial restrictions and competition between the different regions of the country for a fair share of the national budget pie.”

The government, it said, exerted “best efforts” given the circumstances. “Since the gap between those that were planned and those that were implemented is significant, the region should continue pushing for the implementation of urgent projects and the identification of new ones.”