Jose W. Diokno: Fleshing out a legend

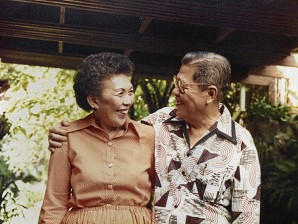

ROMANCE IN ‘SLOW DRAG’. Diokno on wife Carmen: The Lord has never been so good as the day my wife married me. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

(Editor’s Note: As the nation remembers the 1986 People Power Revolution, one family also celebrates the memories of one of Philippine democracy’s towering defenders, Jose W. Diokno—senator, human rights advocate, martial law prisoner, bar topnotcher, man of faith, devoted husband and loving father. “Ka Pepe” passed away 25 years ago, on Feb. 27, 1987. He would have turned 90 today. The following are stories of Diokno written by 7 of his 10 children.)

* * *

Love affair with the law

By Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno

Dad’S love affair with the law started early in his life. As a boy of 12 he would go with his father, Ramon Diokno, to trials in the provinces. He would carry his father’s bag, even had a small chair reserved for him behind the counsel’s table.

The same thing happened to me when I was 13. It was 1974, the height of the Marcos dictatorship, when I first started going to court with Dad. The first time I saw him in action, I was hooked. I knew then, without a shadow of a doubt, that I would become a lawyer. And of course, I wanted to be a lawyer like him.

I learned a lot more watching Dad in and out of court than I did in law school. He was thorough, systematic, and knew his law. A master of trial technique, especially cross-examination. He had a prodigious intellect and could think quickly on his feet. But what stood out more than anything else were his goodness and the strength of his conviction.

He lived the law, breathed it, imbibed it and taught it. And he never abandoned it, even when he was jailed without charges in 1972 and the Marcos-controlled Supreme Court unjustly refused his plea for liberty.

But he did much more than that. Faced with a repressive regime that used the law to suppress the people’s rights, he realized that the law could also be used to liberate the people from their oppression. This revolutionary way of legal thinking led him to establish the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) and to imbue it with the philosophy of developmental legal aid—using the law to challenge state policies, practices and institutions that generate mass injustice and human rights violations. Using the law, in other words, to promote the people’s genuine development.

Dad’s love for the law—and vision for the Filipino lawyer—is best expressed in a letter he wrote in 1972 from his prison cell:

“A lawyer lives in and by law; and there is no law when society is ruled, not by reason, but by will—worse, by the will of one man.

“A lawyer strives for justice; and there is no justice when men and women are imprisoned not only without guilt, but without trial.

“A lawyer must work in freedom; and there is no freedom when conformity is extracted by fear, and criticism silenced by force.

“A lawyer builds on facts. He must seek truth; and there is no truth when facts are suppressed, news is manipulated and charges are fabricated.

“Worse, when the Constitution is invoked to justify outrages against freedom, truth and justice, when democracy is destroyed under the pretext of saving it, law is not only denied—it is perverted.

“And what need do our people have for men and women who could practice perversion?

“Yet the truth remains true that never have our people had greater need than today for great lawyers, and for young men and women determined to be great lawyers.”

Dad often quoted Karl Llewellyn’s statement that a lawyer with technique but without ideals is a menace, while a lawyer with ideals but without technique is a mess; and that we must put technique to work upon the ideals, with vision.

* * *

Mealtime as art, communion

By Maitet Diokno-Pascual

Before Dad taught me anything about law and politics, he taught me about food. I remember him coming home (Baclaran at that time) for lunch, often late, after we’d all eaten. He’d have to wait for Maring, our cook, to heat up his food. While waiting, he’d finish his cup of rice. He had an art of eating this simple cup, such that those of us watching him would get hungry again and join him for lunch “Take Two.” Similarly, he’d eat liver steak with such gusto that, as a kid, I was convinced that it was yummy.

Dad introduced us to the pleasures of Spanish food, like angulas, the white embutido, galantina and chorizos. He liked Filipino food as well. What fascinated me most was watching him eat rice with gatas ng kalabaw (carabao’s milk), raw egg and tapang usa (venison). This I have yet to try; it was enough for me to watch him relish every bite of it.

Dad also loved chocolates. I learned to bake brownies and tried my hand at fudge and baked Alaska because I knew he liked eating them. The praises he heaped upon me for my efforts of course spurred me to keep on baking.

Not only was food important to dad and our family, communion around food fed our minds and souls, too. Sitting around the table with our parents at mealtime was always an opportunity to listen, learn and speak up. Many a journalist and activist who’d visit Dad would inevitably find herself or himself joining the family for lunch or dinner, which made our meals that much more interesting and exciting.

* * *

Roses from prison

By Maia Diokno

Dad was very much a family man and a homebody. Before martial law, the whole family would spend entire summers either at the beach, or in Baguio. Dad would shut down his law office, and the family, his staff and their families would convoy down to Matabungkay.

Martial law and Dad’s detention stopped those family vacations, but on special occasions we were allowed to spend the day with him at Fort Bonifacio. During those visits, he would proudly show off his newly acquired skills in gardening (each time his roses would bloom, he would say his release was nearing), cooking (admittedly, with some difficulty) and cleaning. He would later tell us that his saddest moments were when we would leave him behind in his cell.

Dad loved to give us presents. While in prison, he would send us letters as birthday presents, adding roses he had grown or little craft projects he had worked on himself. His letters were highly personal, and showed that he knew what was going on in our lives, our heads and our hearts. He thought about us while he was in isolation in Laur, composing a poem for my brother’s birthday entirely in his head (he wasn’t allowed pen and paper), and sharing the poem with us from memory when he was finally returned to Fort Bonifacio.

After his release, whenever he would travel, he would buy each of us presents, spending time choosing what he thought would suit each child and grandchild. Though Dad was always busy with his work, he was there when we needed him. In my first year in high school, my section had a weekend class trip to Batangas, which required parental supervision. Knowing how busy he was (this was at a time when Dad was handling human rights cases and giving speeches), I hesitantly asked Dad and Mom (Carmen) if they were willing to watch over a gaggle of 14-year-old Assumptionistas. They readily said yes, and I still remember that weekend, Dad in his beachwear (matching shirt and trunks), carrying his camera and taking photos of me and my friends.

Dad knew that he was asking a lot from us; his work often took him away, sometimes into situations that weren’t safe. He recognized our sacrifices, valued our support, and acknowledged that he was learning from us, as well. In one letter to Mom, he said that we had taught courage, hope and determination and added: “Thank you, above all else, for being you—each of you—and for being mine.” He ended this letter, and every letter he wrote us with a simple, “Love, Dad.” And that was all he needed to say.

* * *

‘Pepe’ and Mom’s slow dance

By Cookie Diokno

Dad and Mom met after the war at a party hosted by a mutual friend, the rambunctious Manila Mayor Arsenio Lacson. Arriving at the party with their respective dates, Lacson introduced Dad and Mom to each other and seated them at the same table. Instantly attracted to the other, Dad and Mom promptly forgot their dates and spent the entire evening getting to know each other. That meeting became the first of many.

Dad invited Mom on dates, mostly to watch movies and share dinner, properly chaperoned by Mom’s two younger sisters. Theirs was some romance—two intelligent, strong-willed individuals who became true friends at first, and later partners for life. In the course of the courtship, Dad was rewarded by his parents with a trip abroad for having topped the bar exam. Mom pined for him, subsisting on beautiful love letters from a distance. (From courtship till death, Dad began every letter to Mom with “My Darling” and ended with “Yours, Pepe.”) Dad returned home to find Mom seriously ill; marriage soon followed.

Dad was the more affectionate of the two. They both enjoyed Spanish love songs; while listening, Dad would sometimes take Mom and dance with her (the old “slow drag”) while we children played mindlessly.

Ten children later plus grandchildren in tow, and writing from prison, Dad described what he loved about Mom: “Her common sense, her practical approach to things, her courage and her love for us that have enabled her to bear the difficulties and humiliation of these months, not only without complaining or despairing, but with proud dignity and firm hope…” Mom was the reason why “life in prison—lonely and boring and senseless though it may be—is still worth living.”

No greater tribute did Dad give to the love of his life than these words: “The Lord has always been good to me, but never so good as the day your mother married me.”

* * *

Our walking ‘Wikipedia’

By Maris Diokno

Long before Wikipedia, we had Dad, our in-house walking, breathing powerhouse of information. Afraid we would rely on him forever for meanings of words we didn’t understand, he frequently admonished us to “look it up in the dictionary.” But it wasn’t just word meanings we ran to him for; we would ask him virtually anything and it was rare that we heard the response, “I don’t know.” This was because he read voraciously, whether for work or pleasure, with a quiet passion.

Dad brought us into the world of knowledge as early as we learned to read. We spent Sundays trooping down to Peco, the bookstore of old (long before National Bookstore), where we spent hours browsing through books before we each took home our private loot. Then in Dad and Mom’s room, we would start reading our books, spread out flat on the floor, stomachs pressed down and elbows propped up, feeding our minds until it was time to eat.

Dad’s library was the epitome of thirst for learning. Dad didn’t collect books; he bought them to read them, and nothing was on display in his library that he hadn’t read. Before martial law he had two libraries: one at home, which spanned just about every topic I can recall, from judo to psychology, economics and politics; and his law library in his office, which occupied half a floor. He had thousands of books and ordered new ones every month, each of them duly catalogued by his office librarian. So familiar was Dad with his books that when he was imprisoned during the dictatorship, he would tell us which book to bring him and on which shelf of his numerous bookcases we would find it.

To our horror, Dad’s office on MH del Pilar was burned while he was in prison, and because of curfew during martial law (starting 9 p.m.), we were only able to go to his office after 4 a.m., when it had already burned. Thankfully, a couple of weeks before it was burned, my mother (guided by strong intuition) decided to transfer Dad’s library to the house. Those were difficult weeks, for Dad would ask for books still piled up at home. When Mom told Dad that his office was burned, she quickly assured him that his books were safe. Behind prison bars, this was some consolation.

On his visits abroad after his release from prison, often to address human rights organizations, Dad spent hours on end hopping from one bookstore to another. Aside from the court, the bookstore/library was his other world, and he loved it. The habit of reading was one we children acquired by sheer osmosis. Dad and Mom never forced us to read; we just saw them read all the time.

* * *

A promise to God

By Mench and Pat Diokno

Dad was such an intellectual that it would probably surprise many to learn that he was a deeply spiritual person. His faith was very personal and private; he did not preach and as we children grew older, he left the practice of our faith to each one of us, without judging us for our sometimes lack of fervor.

Dad, too, had a deep respect for other faiths and could be with any religion comfortably, and even with those who professed no faith at all.

When we were younger, Holy Week, especially Holy Thursday and Good Friday, were special days. We would all get dressed on Holy Thursday and visit churches in Manila or sometimes in Batangas. On Good Friday, whether vacationing at the beach in Matabungkay or at home, the minute it was 3 p.m. we would all be seated together with the Bible open and take turns reading portions of the Bible aloud (unless Dad read it himself). A brief period of silent meditation followed the reading.

Dad and Mom had a devotion to St. Jude Thaddeus and San Martin de Porres. During martial law, a group of political detainees gifted Dad with a bamboo mural they had made of St. Martin de Porres. This hung in Mom and Dad’s bedroom, which Mom kept hanging even after Dad’s passing.

St. Jude, the saint of the impossible, was a frequent recipient of Dad and Mom’s entreaties. This we completely understood, given the challenges they faced raising a brood of 10 and then caring for a larger community of partners in struggle during martial law. We used to pray the 40-day novena to St. Jude as a family, led by Dad. As we kids had difficulty completing the novena, Dad and Mom faithfully completed theirs. On the night he was arrested, we had just finished praying the novena as a family.

Dad never left the house without his rosary in his pocket, a habit, according to a La Salle Brother, that Dad had picked up in school. Even under detention during martial law and in solitary confinement at Laur, Dad had his rosary with him. In fact, he had to ask his guards for his rosary whenever he wanted to pray, since he was not allowed to keep anything in his room.

One of the things Dad told us when we finally saw him in Laur after a month of no word from him or of him, was that he had made God a promise that if he got to see us again, he would attend daily Masses for a month. Since he could not do this himself, he asked us to do it for him—which we did. Monday was for the Holy Spirit; Tuesday, San Martin de Porres; Wednesday, St. Joseph; Thursday, St. Jude Thaddeus; Friday, Sacred Heart; and Saturday, Mama Mary.

After his release from prison, Dad plunged immediately into human rights work and the movement to remove US military bases. He never lost faith. When he learned he had cancer, he faced his mortality even as he fought the disease. He never lost faith.

* * *

(FLAG is holding a series of activities paying tribute to the late Senator Diokno till Feb. 29. For inquiries, call (632) 9205132 or send an e-mail to [email protected].)