Rizal: ‘Amboy’ or home-made hero?

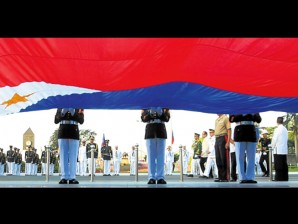

President Aquino troops the line during the flag-raising rites on the 115th death anniversary of national hero Jose Rizal at Rizal Park in Manila on Friday. Rizal was sentenced to die by firing squad by the Spanish colonial government after he was convicted of treason for advocating independence and of sedition for inciting armed revolution. EDWIN BACASMAS

One hundred and fifteen years after Jose Rizal was executed by the Spanish colonial regime, controversy still rages as to whether he was a reformist or a revolutionary.

Rizal is immensely influential to generations of Filipinos. How he is viewed can help define the course of our history.

In his Rizal Day Lecture on Dec. 30, 1969, titled “Veneration Without Understanding,” the historian Renato Constantino noted it was American Governor General William Howard Taft who in 1901 suggested to the Philippine Commission the naming of a national hero for Filipinos.

Subsequently, the US-sponsored commission passed Act No. 346 which set the anniversary of Rizal’s death as a “day of observance.”

Constantino cites Theodore Friend in his book, “Between Two Empires,” as saying that Taft “with other American colonial officials and some conservative Filipinos chose him (Rizal) a model hero over other contestants—Aguinaldo too militant, Bonifacio too radical, Mabini unregenerate.”

Filipinos chose him

The rationale for naming Rizal as the Filipinos’ national hero by the American administration was articulated by US Governor General W. Cameron Forbes in his book, “The Philippine Islands,” also cited by Constantino. Forbes wrote:

“It is eminently proper that Rizal should have become the acknowledged national hero of the Philippine people. Rizal never advocated independence, nor did he advocate armed resistance to the government. He urged reform from within by publicity, by public education, and appeal to the public conscience.”

But in truth it was the Filipinos and not the Americans who first chose Rizal as their national hero. It was revolutionary President Emilio Aguinaldo of the First Philippine Republic—not Taft and the Second Philippine Commission—who first designated Rizal as a national hero.

First monument

On Dec. 20, 1898, while the First Philippine Republic was still in control of all of the Philippine archipelago, except US-occupied Manila, Aguinaldo promulgated a decree proclaiming Dec. 30 as a “national day of mourning in memory of Rizal and other victims of Spanish tyranny.”

While not only Rizal but “other victims of Spanish tyranny” were to be honored, the fact that it was on his death anniversary that the celebration was to be held showed that Rizal was the center of the celebration, just two years after his death.

The first official observance of Rizal Day was held on Dec. 30, 1898, in Manila. Simultaneously in rites in Daet, Camarines Sur province, the first Rizal monument was unveiled. The statue, which still exists today, was erected through the voluntary contributions of revolutionary leaders and nationalistic townspeople.

Thereafter, practically all Filipino towns would bloom with Rizal monuments and their main streets named after Rizal as a spontaneous expression of our people’s recognition and reverence of Rizal as their primary national idol. He was, at that point, generally acknowledged as the inspiration, if not instigator, of national independence and unity.

Independence was proclaimed by Filipinos themselves in Kawit, Cavite province, six months earlier on June 12, 1898, ending three and a half centuries of Spanish rule. The US then still had to consolidate its occupation of the entire archipelago.

Started as reformist

True, like most revolutionaries in world history, Rizal started out as a reformist. Together with Graciano Lopez Jaena, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Antonio Luna and Mariano Ponce, he founded in 1899 the newspaper La Solidaridad, which became in Madrid the Filipinos’ mouthpiece in demanding reforms in Spain’s governance of the Philippines.

The “propagandists” at first advocated the elevation of Filipinos from the status of subjects to citizens of Spain, with equal rights. They asked for representation of the Philippines in the Spanish Cortes, or Parliament. This by itself was revolutionary because when a slave demands to be equal to his master, it is a revolution. But it was still short of the demand for national independence.

But in history, reformists ultimately morph into revolutionaries and separatists when their demands for reform, justice and equality are rejected.

Thus, in their Declaration of Independence, the US founding fathers stressed that before taking up arms, they had peaceably petitioned for reforms.

Parallel lives

Rizal was among the first of the Propagandists (as the Reformists were then called) to realize that Solidaridad was not getting anywhere in its media campaign for reforms. He took a leave from the newspaper to devote his time to writing a novel (“El Filibusterismo”) that would more dramatically denounce the tyranny of the Spanish regime, and thus arouse the fury and ignite the latent nationalism of the Filipinos into the conflagration of revolution.

His first novel, “Noli Me Tangere,” which had caused a stir and made him the “enemy” of Spanish colonialists, depicts the futility of seeking reforms through education as such efforts would only be frustrated and sabotaged by the government and its crafty mentors, the friars.

In “El Filibusterismo,” the hero/reformist Ibarra morphs into the terrorist/revolutionary/separatist Simoun. A tight parallel could be drawn between the real life of Rizal and the fictional life of Ibarra-turned-Simoun.

Mabini, an erudite lawyer and scholar, correctly read the real message of Rizal’s novels. In his book, “The Philippine Revolution,” Mabini, a Manila correspondent of the Madrid-based Solidaridad and dubbed as the “Brains of the Revolution,” wrote:

“… Rizal in particular gave two pieces of advice … the first, he served notice on the Spaniards that if the Spanish government, in order to please the friars, remained deaf to the demands of the Filipino people, the latter would have recourse in desperation to violent means and seek independence as relief for their sorrows; and in the second, he warned the Filipinos that, if they should take up their country’s course motivated by personal hatred and ambition, they would, far from helping it, only make it suffer all the more.”

Mabini cited Elias, the radical peasant of Rizal’s novels, who advocated independence through revolutionary violence, as the model rebel leader.

Preaching revolution

In his prophetic essay, “The Philippines a Century Hence,” Rizal more explicitly expressed his stand. He warned that “if equitable laws and sincere and liberal reforms” were denied by the Spanish government, “the Philippines one day will declare herself inevitably and unmistakably independent … after staining herself and the Mother Country with her own blood.”

In a proclamation addressed to “Our Dear Mother Country, Spain,” Rizal was even bolder. He thundered: “When a people is gagged; when its dignity, honor and all its liberties are trampled; when it no longer has any recourse against the tyranny of its oppressors; when its complaints, petitions and groans are not attended to … then …! then …! it has left no other remedy but to take down with delirious hand from the infernal altars the bloody and suicidal dagger of revolution!”

Declaration of independence

Another major revolutionary who believed Rizal was preaching revolution was Bonifacio. He was one of those present at the founding of the La Liga Filipina organized by Rizal on July 3, 1892, a week after his return from Hong Kong, in spite of the warning that he might be killed or imprisoned by the Spaniards. The constitution of the La Liga Filipina was in actuality a separatist document, a virtual declaration of independence.

The purposes of the League of Filipinos were: “To unite the whole archipelago into one compact; Mutual protection in every case of trouble and need; Defense against every violence and injustice; Development of education, agriculture and commerce; Study and implementation of reforms.” These purposes would be carried out by a Filipino Supreme Council, provincial councils and popular councils.

In effect, Rizal was proposing a separate government. In the indictment of treason against the Spanish regime, the formation of the Liga was one of the charges against him.

Within three days after the founding of the Liga, Rizal was arrested and exiled to Dapitan. The authorities correctly apprehended that Rizal had transgressed the bounds of reformism, stepping into the dangerous grounds of revolution.

Peaceful means pointless

Indeed, his exile was the blow that convinced the followers of Rizal that seeking reforms through peaceful means was pointless.

On the night of July 7, 1892, Bonifacio and other members of the Liga formed the Katipunan society (Kataastaasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan), with independence through armed revolution as its main objective. Rizal was made honorary chair and his name was used as a password by members of the secret society. He was, if not their actual leader, their spiritual leader.

Four years later, with the Katipunan membership having grown by leaps and bounds, no doubt due in part to the general belief that Rizal was behind the movement, Bonifacio sent Dr. Pio Valenzuela, a member of the supreme council, to Dapitan to get Rizal’s “approval” for the start of the uprising.

The decision to consult Rizal was made collectively during a secret conclave in bancas of 60 Katipuneros on May 6, 1896, in the then remote sitio of Ugong, north of the Pasig River. Present were Bonifacio, the KKK supremo, and Aguinaldo, who led the revolution successfully for a time after the assassination of Bonifacio.

‘So the seed grows’

Rizal and Valenzuela conversed conspiratorially in a shady nook away from Rizal’s house on June 21, 1896. According to an account by Arturo E. Valenzuela Jr., based on the memoirs of his grandfather Pio, Rizal was elated by the news of the Katipunan’s existence, and murmured, “So the seed grows,” ecstatic that the seed of revolution he had sown was sprouting.

Historian Teodoro A. Agoncillo, in his book “History of the Filipino People,” noted that Rizal, in his talk with Valenzuela, gave no objection to armed revolution, but only cautioned that if an insurrection was to be staged, all efforts should be exerted to gather sufficient arms in order to ensure success and avoid unnecessary casualties and sufferings of civilians and insurrectionists.

He also suggested that Antonio Luna, a reformist who had studied military science in Spain, be recruited as a military leader of the revolution.

“It is obvious,” observed Agoncillo, “that Rizal was not against revolution itself but was only against it in the absence of preparation and arms on the part of the rebels.”

Premature launch

Indeed, Bonifacio and his council took pains to implement Rizal’s advice, contacting Luna and informing him of Rizal’s wish. Unfortunately, Luna turned down the invitation. He later joined the revolutionary army in the war against the United States.

Two months after Valenzuela’s meeting with Rizal, on Aug. 19, the Katipunan was betrayed to Tondo parish priest Fr. Mariano Gil, prompting the authorities to round up suspected members of the secret society. This forced Bonifacio to prematurely launch the uprising on Aug. 22 in Pugadlawin through the unsheathing of bolos and the tearing of cedulas (residence certificate).

This turn of events cut short Bonifacio’s efforts to implement Rizal’s advice to make full preparations before launching a revolution. He had, as a matter of fact, written several rich Filipinos to support the Katipunan, although many refused him and even threatened to expose the plot.

If it were not for the betrayal of the KKK by the wife of one of two quarreling members of the Katipunan to a priest who violated the sanctity of the confessional, the revolution could have been launched at a more propitious time.

Rizal’s intention

Those who claim that Rizal was against revolution point out that he was on his way to Cuba to work as a military doctor in the Cuban revolution when the Katipunan revolution broke out. Rizal’s detractors claim he was trying to flee from involvement in the revolution.

In his book, “Dr. Pio Valenzuela and the Katipunan,” Arturo Valenzuela Jr. narrates that during the conversation between his grandfather Pio and Rizal, the latter had felt impelled to disclose that a year earlier, in June 1895, he had written Governor General Ramon Blanco, applying to serve as a doctor in the Cuban revolution.

“My intention,” Rizal whispered to Pio, “…is to study the war in a practical way, to go through the Cuban soldiery and find something to remedy the bad situation in our country. Then after a time, I would return to our native land when necessity arises.” In short, he was preparing himself for the revolution.

Rizal received the permission of Blanco on July 30, two weeks after Valenzuela had left. Austin Coates, in his excellent biography of Rizal, said he was at first reluctant to leave. But because of the prodding of his family, Rizal departed Dapitan on the steamer España on July 3. He had no knowledge that the revolution would break out in two weeks.

On arrival in Manila, still on exile, he was kept under ship arrest in a Spanish cruiser on Manila Bay for a month, until he sailed on the Isla de Panay for Cuba. Thus he had no news of the revolution. On Sept. 28, a day off Port Said, he was arrested by the ship’s captain, taken to Barcelona, Spain, where he was incarcerated and returned to Manila on Dec. 3.

Questioned manifesto

Much is made by the detractors of Rizal of his “Manifesto” to the Filipino people dated Dec. 15, 1896, while he was already imprisoned at Fort Santiago. In the “Manifesto,” Rizal denied responsibility for the revolution, claiming he had opposed it from the very beginning because he had believed in its “impossibility.”

This was a half-truth as we have seen. Valenzuela’s recollection showed that initially Rizal was opposed to the revolution but when told that the movement could no longer be stopped, he gave advice as to how it could have better chances of success. He suggested that rich Filipinos be tapped to finance the purchase of more arms.

Besides, Rizal never betrayed his knowledge of the plot to the authorities, making him at the very least an accomplice, while his positive advice to the revolutionaries to gather more arms made him a co-conspirator.

For defense attorney

The “Manifesto,” intended for the use of his defense attorney in his trial, must also be viewed from the circumstance of its writing. Not only did he face a death sentence, Rizal must have also been thinking of trying to save his family from further persecution.

His beloved brother Paciano had already been tortured almost to death in Fort Santiago by the authorities in a vain attempt to make him implicate Rizal. More important to him than his life was the safety and security of his family. This made him return to the Philippines in July 1892 despite his foreboding that he would lose his life in the process.

Any document signed under such circumstances must lack credibility or veracity. In fact, the Spanish government never released it, not believing in its truthfulness. Instead, the government convicted him of treason for advocating independence and of sedition for inciting an armed revolution.

Haunting poem

Rizal’s real feelings about the revolution and its separatist aim can more truly be gleaned from his haunting poem, “My Last Farewell,” which was written by him just hours before his execution, and intended only for the eyes of his countrymen and not for his judges.

In that final epic poem, he devoted a paean of praise for the revolutionaries.

After gladly offering his life to his country in the first stanza—“had it been a life more brilliant, more fine, more fulfilled, even so it is to you, I would have given it, willingly to you”—he wrote:

Others are giving you their lives on fields of battle,

Fighting joyfully without hesitation or thought for the

Consequence,

How it takes place is not important. Cypress, laurel or lily,

Scaffold or battlefield, in combat or cruel martyrdom,

It is the same when what is asked of you is for your country

And your home.

(Translation from Spanish by Austin Coates, author of “Rizal: Filipino Nationalist and Martyr.”)

Icon of all

Rizal is an icon and a martyr for independence and freedom not just of Filipinos but of all the oppressed peoples in history who have hungered, struggled and fought for liberty, dignity, enlightenment, and social and economic justice. He richly deserves the highest berth in our pantheon of heroes. All other nationalist Filipino heroes stand proud beside him.

There is no need to pit our heroes against each other for they stand equally on the hallowed ground of patriotism and nationalism.

(The author is a veteran journalist, former editor of the Philippine Graphic and of the defunct Philippine News Service, which was closed by the Marcos dictatorship, and a political detainee under martial law. He is also spokesperson of the Movement for Truth in History, with e-mail address at [email protected].)