BIRD RESCUE In 2014, Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) personnel recovered three endangered Philippine eagles, six cockatoos and an amethyst brown dove from wildlife traders in Talisay City, Cebu province. Birds, according to records of the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau from 2013 to 2018, comprised the fourth largest seizure from illegal traders in the country after reptiles, mammals and anthropods. —TONEE DESPOJO/CEBU DAILYNEWS

(Last of three parts)

MANILA, Philippines — An unassuming house with high walls in Pasay City has been a longtime target of environmental law enforcers.

Last year, a raid that followed an entrapment operation revealed the house’s secrets: hundreds of birds, from black palm cockatoos and rainbow lories to young emus and even a baby ostrich, in cages that lined the walls, and, in other enclosures, more than 100 sugar gliders, small marsupials similar to flying squirrels, and two small wallabies, members of the kangaroo family.

Most of the animals were believed to have been smuggled from Indonesia through Mindanao. They were collectively valued at P10 million and were reportedly to be sold online, through social networking sites like Facebook.

For many enforcers, raiding the house offered a sense of déjà vu. It was the subject of their search once in 2014, and again in the following year. In those three raids in the past five years, authorities were greeted by familiar sights: all sorts of endangered mammals, birds and reptiles from Palawan province and other countries, crammed in metal cages all over the house.

At the center of it is the homeowner himself, who authorities identified as Abraham Bernales. Since 2011, wildlife law enforcers from the Department of Environment and National Resources (DENR) and agents from the National Bureau of Investigation and the Philippine National Police had been repeatedly arresting and charging Bernales with violations of the wildlife law.

Yet records show that in the four times he was collared for illegally transporting, possessing and trading wildlife, there had been only one conviction, for which he had to cough up a P5,000 fine.

Poor conviction rate

Bernales’ repeated evasion of the law shows the weaker link in the government’s pursuit of wildlife traffickers. Despite numerous seizures and apprehensions through the years, prosecuting wildlife criminals remains a daunting challenge, allowing kingpins to go scot-free and the illegal trade to persist.

Since the passage in 2001 of Republic Act No. 9147, or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, authorities have been doggedly going after wildlife traffickers and illegal traders.

Major confiscations had since been recorded, resulting in the seizure of over 3,000 pangolins, the most trafficked mammal in the world; more than 5,000 freshwater and sea turtles, including some 4,000 critically endangered Philippine pond turtles; and hundreds of birds, including those endemic to Palawan, and others poached and trafficked from other countries like Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

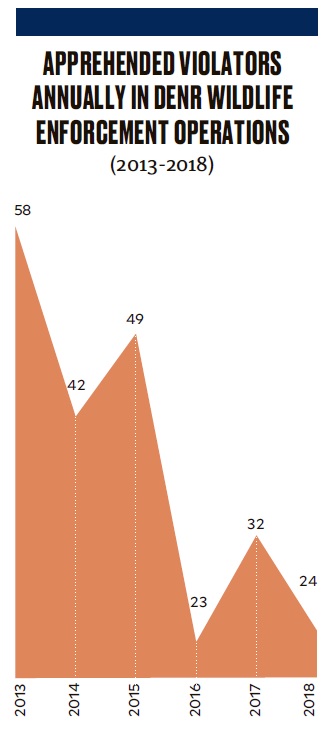

From 2013 to 2018, at least 123 enforcement operations had been conducted by authorities, leading to more than 26,700 confiscated wildlife, records from the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau showed.

But in that six-year span, only 70 cases against wildlife criminals had been filed, with only 18 convictions during the period. Of 228 identified violators, only 30—a mere 13 percent—had been penalized.

Whether any of them had actually spent time in jail is another question, since the sentences that were meted out varied significantly from case to case, records showed. Some were merely ordered to pay fines ranging from P250 to P50,000. Others were jailed for five days, some for six months to a year.

But both enforcers and wildlife experts said most of the offenders did not actually do jail time because they would post bail as soon as they were charged. First-time offenders would apply for probation upon indictment because the penalties for illegal trading and trafficking all fall below imprisonment of six years.

“We have paper convictions,” said Emerson Sy of the Philippine Center for Terrestrial and Aquatic Research. “Some traffickers also know the ins and outs of the judicial system … [For big-time criminals], bail is just spare change. Once they are out, they just continue with their illegal activity.”

In Bernales’ case, he sought probation in an earlier charge, authorities said. In succeeding arrests, he skipped jail time by using another loophole: Being elderly, he could cite humanitarian grounds.

Bernales has repeatedly denied the charges filed against him through the years. In all his arrests, he insisted that he was a mere caretaker of the hundreds of wild animals caged in his home.

He owns a pet shop at Cartimar Market in Pasay.

Familiar issues

The issues that plague environment cases are the same ones that beset the judicial system: overloaded courts, slow-paced trials and technicalities.

Still, significant efforts have been made through the years to address the prosecution of environment crimes, including illegal trading in wildlife. In 2010, the Supreme Court issued the rules of procedure for civil, criminal and special civil actions involving violations of environmental laws and related legislation.

“The whole goal was to hasten the process of filing cases and for the courts to make their decisions the soonest possible time,” said lawyer Edward Lorenzo, who serves as wildlife crime prevention adviser for USAID Protect Wildlife. “It came about from the experience of groups, prosecutors and enforcers that some violators escape after bail is filed, then their cases are archived.”

Dragging cases also take their toll on enforcers who may be reassigned elsewhere and thus fail to continue attending trial as witnesses.

The provision for continuous trial has speeded up most of the cases. But many still take a long time to be resolved because regional and municipal courts are overburdened with other cases, Lorenzo said.

In 2008, the Supreme Court approved the creation of 117 environment courts. Yet these “green courts” do not hear environment cases exclusively; often these cases are lumped together with other criminal cases, such as homicide and robbery.

Despite existing legislation, the zeal to prosecute environmental offenders may be less compared to prosecuting a person who has committed a crime against another.

“Even without a law, when you punch someone, you feel bad because [the laws that govern the act] are based on moral law,” said lawyer Asis Perez, senior adviser of Tanggol Kalikasan.

“In terms of wildlife, there is none,” Perez said. “Our basis is our deep apprehension now that these animals are becoming extinct. That takes some time to be ingrained in our consciousness … There is still some convincing that needs to be done.”

No appreciation

According to environment lawyers and groups, a crucial step toward better prosecution is training prosecutors and judges in handling environment cases, especially those involving wildlife. In most law schools in the country, environmental law has yet to be integrated in the program, and professional training courses are few and far between.

“Sometimes, one of the issues with prosecutors is that there is no appreciation of wildlife cases. Some would think it’s just a bird or a pet,” Lorenzo said. “But with training, they [will] see what is at stake, that there are far-reaching complications.”

This may also help deal with a lingering challenge in prosecuting illegal wildlife cases: determining the value of the confiscated animals, which sets the gravity of the fines and penalty for the accused.

Often, the prosecution only relies on the market value of the poached wildlife, without factoring in what humans and the environment may lose once these animals are removed from their habitats.

“It is difficult to peg a value, thus it is difficult to peg the punishment,” said lawyer Mary Kristerie Baleva, external relations and policy specialist at the Asean Centre for Biodiversity (ACB). “You may have monetary value for one, but the value in terms of biodiversity is difficult to determine.”

In most cases, even if hundreds of animals of different species are seized from a smuggler or trafficker, the offense is still counted as a single violation of the wildlife law, potentially leading to convictions that undermine the value of what was taken from the wild.

In most cases, even if hundreds of animals of different species are seized from a smuggler or trafficker, the offense is still counted as a single violation of the wildlife law, potentially leading to convictions that undermine the value of what was taken from the wild.

For instance, a municipal trial court judge in Mati City, Davao Oriental province, recently convicted two men of illegally possessing and trading wildlife. When they were arrested in April, authorities seized 450 different species of animals poached from Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, including the critically endangered western long-beaked echidna, a rarely spotted egg-laying mammal. The value of the wildlife was estimated at P50 million.

Despite the eye-popping number of confiscated animals, the two men were meted a jail term of up to four years and a fine of P30,000 each.

Said Baleva: “For example, you placed the value of a seahorse at P10. If you look at its biodiversity value, it’s difficult to determine the breadth and depth … of the damage to biodiversity and ecosystem services because of the trafficking of even one single animal.”

“It’s possible that you have only three remaining individuals of a certain species,” she said.

The threat of extinction of certain species, however, still appears lost to the prosecution. Just last month, three men who smuggled 10 Philippine pangolins and who were arrested in Tagaytay City were sentenced to jail time of only three months and told to pay a P20,000 fine each. Freed on bail, they have since sought probation.

But the true value of the endemic pangolins remains to be seen, even as their population is dwindling fast amid little knowledge about them.

Stiffer fines

To further strengthen the prosecution, experts and advocates said, the wildlife law must be amended to further stiffen penalties and also train environmental law enforcers to go after traffickers and illegal traders.

In the imposition of penalties, the law takes into consideration both the act and the conservation status of the animals. For example, illegal trading can lead to a jail term of up to four years and a fine of P5,000 to P300,000, if the species are listed as critical.

“[But] the fines are not clear: Does the fine correspond to one animal or to many individuals?” said ACB executive director Theresa Mundita Lim. “The services that the animals provide must also be taken into account.”

A draft amendment pending in the House of Representatives aims to raise the penalties, both fine and imprisonment, for different illegal activities concerning wildlife, including killing, trade, collection and transport. Under the proposed amendment, trading critical species can now lead to jail time of up to six years and fines ranging from P50,000 to P600,000.

Along with consistent confiscations, these stiffer penalties and longer jail terms can serve as deterrent to criminals, Lim said.

Despite the challenges in prosecution, the Philippines is moving toward the right direction in curbing the illegal wildlife trade.

“We have come a long way since 20 years ago. We just need to be vigilant and include the consumers in the equation so they do not patronize illegally traded species,” Lim said.

But with criminals taking advantage of both new technologies and shortcomings in the prosecution, the pressure remains for the government to work much faster.

Said Lorenzo: “Usually, all governments play catch up with the ‘iligalista’ (wildlife trader) because they are the ones innovating. When they change their strategy, the government should also do so. But the question is, how fast do we work to catch up?”

* * *

STOP WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING

Report wildlife crime by calling the Department of Environment and Natural Resources-Biodiversity Management Bureau at (02) 925-8952 or (02) 925-8953, or reach them via Facebook at face

book.com/denrbiodiversity.

The Environmental Crime Division of the National Bureau of Investigation can also receive reports of illicit activity against wildlife.

For cases in Palawan province, the public can reach out to the enforcement team of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development via mobile, at 0935-1162336 (Globe/TM) or at 0948-9372200 (Smart/Talk and Text).

Anonymous tips, including screenshots showing illegal online activity, can also be sent to several wildlife monitoring groups on Facebook, such as the Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines, Pinoy Naturalist and the Philippine Wildlife Trade Monitoring Network.

New Filipino wildlife traffickers, traders emerge in FB hubs